My father always loved science fiction. He still does, but the events I'm going to relate occurred in the past, so I'm going to use the past tense here. When I was about 6 or 7 years old I was fascinated by a catty-corner bookshelf in our house that was packed with paperback books. Made of reddish-brown wood and mirrored in the back (so the books looked like double rows on each shelf), it stood three or four-tiered in the corner of a cluttered "music room" containing an upright piano and nearly the entire published output of the G. Schirmer Inc., Music Company, then one of the best known publishers of classical music books, and a room my brothers and I all learned and studied the piano under our father's tutelage.

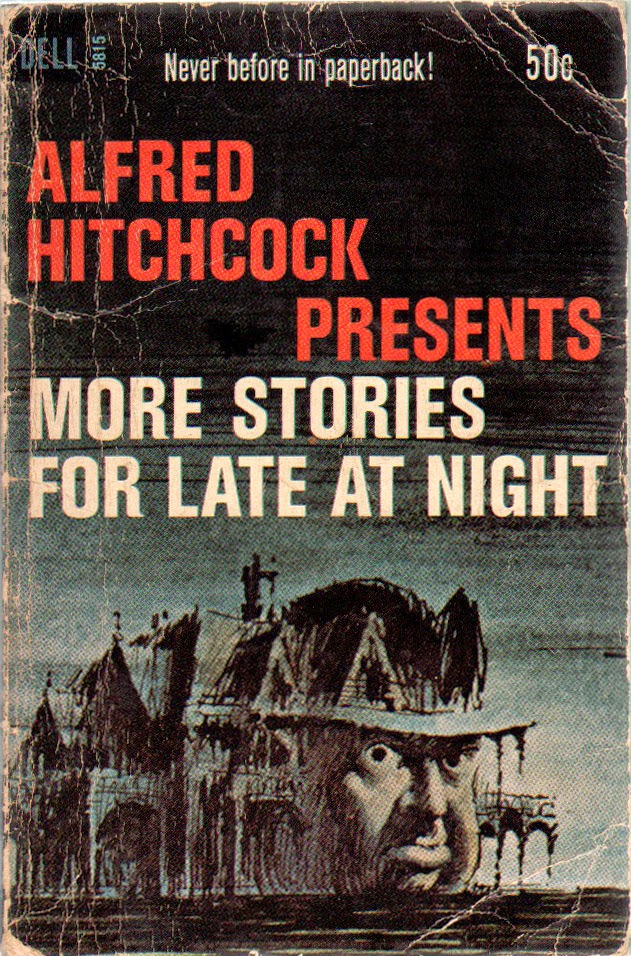

I would sit down on the floor in front of that bookshelf and pull out books, enthralled by the strange covers, images of weird creatures and ethereal space scenes. The publishers, titles and authors meant nothing to me, ..... Ballantine, Pocket, Lancer, Dell, Avon, and those cool double books from Ace ..... Expedition to Earth, Shock, The Dunwich Horror and Others, The Unhumans ..... Lovecraft, Asimov, Bradbury, Derleth, Matheson, Clarke. The books were seemingly endless and shelved in no particular pattern or order. Here are some actual examples of the originals on that shelf:

90% of the books were anthology compilations as my dad preferred them to longer sci-fi novels, finding it easier to get a complete story read in the down time he had. His favorite authors, hands down, were H.P. Lovecraft and Arthur C. Clarke. Now at that age I really couldn't read them and there were no pictures inside, except for one book by Ray Bradbury (with a gorgeous Frank Frazetta cover!) that did indeed have comic book type pictures of the stories (advertised as such on the cover, they were actually old E.C. Comics reprints).

In the evenings, when my brothers and I went to bed, our father would often tell us stories in the dark, as any parent would do to his young children. Once in a while the stories were read out of a book with a flashlight, although most were seemingly made up on the spot, or as I later found out, many weren't. But the stories were often quite frightening and I'm certain I wasn't the only one who found sleep difficult after hearing stories called "The Peabody Heritage", "The Whistling Room", "Exile of the Eons" or "The Haunter of the Dark". Yes, I would daresay that some of those stories scared the wits out of us as my father set an incredible mood in the pitch blackness, with the consequence that often my mother would poke her head in and yell at him for frightening us.To be fair, he also told or read us stories by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, including stories of Sherlock Holmes, The White Company, and the adventures of Sir Nigel.

But there was one additional book on that shelf that was not a paperback book. It was a hardcover, battered and well-read, with some pages even starting to come loose. The book was plain steel-grey in color and the entire spine was bound in grey duct tape for reinforcement. It stuck out like a sore thumb, on the left-hand corner of the top tier (where it fit because the top was open), propping up the books next to it .There was no colorful picture on the cover (only a strange blue design) and the publisher was Random House, with the year of publication 1946, literally a century ago to a 7 year old. Inside was written in fountain pen ink, the name of the original owner, Seymour D. Nachamis, with several different addresses written on the inside front cover, each scratched out as he moved from Fort Washington Avenue in Washington Heights to Baxter Avenue in Elmhurst (and later to Continental Avenue in Forest Hills).

Seymour was known to our family as Nick Nack, a jazz aficionado friend of my father who frequented jazz clubs in the 1940's through the 1960's, and was somewhat well known as a clubber by jazz musicians of the time in New York, including, Billy Taylor, Mary Lou Williams and Marion McPartland, at venues including The Hickory House on 52nd Street (where my father also played in 1962).

During the second world war, Nick Nack served under Captain Ronald Reagan in Culver City, California, and over the decades, although my dad and Nick Nack's meetings in person were infrequent, they spent hours and hours on the phone discussing jazz, musicians, classic noir films and the latest jokes they'd heard.

(The meetings became more and more infrequent due to the fact that each visit to my parents house often coincided with a potentially serious mishap. 1) Nick Nack was hit (bumped) by a car while waiting for my father to pick him up on Northern Blvd. 2) Nick Nack went into hypoglycemic shock before a backyard BBQ, causing him to be rushed to the hospital. 3) My brother fell down a flight of stairs while carrying a bicycle when Nick Nack arrived one Sunday for dinner. It reached the point where my mother probably felt it was "safer" for everybody if Nick Nack and my father just spoke on the phone.)

|

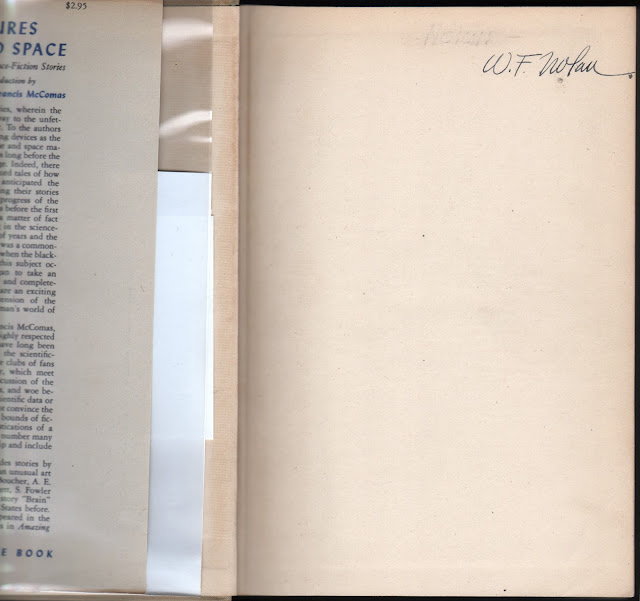

| Inside front cover original owner's signature and addresses: "Nick Nack Copy" |

Nick Nack must have given or loaned the book to my father. There was no title on the cover, instead that weird little blue graphic that made no sense to me. The title was also on the spine and visible by virtue of a window of gray duct tape cut out. In fact, I guarantee it was my father who duct-taped the book together, probably frustrated that the book given/loaned to him was literally falling apart. Archival? No, but the book is still together as can be seen.

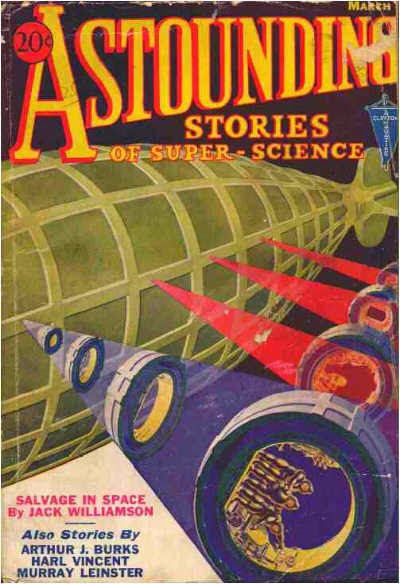

Inside I found the title, Adventures in Time and Space: An Anthology of Modern Science Fiction Stories. The book was massive, nearly 1000 pages and filled with 35 stories, some with authors I recognized from the paperback books. The volume was beat up, sparse and enigmatic to me. What intrigued me further was that every story in this book had been published even longer ago, in a strange sounding magazine called Astounding Stories, in the 1930's and 1940's (actually, from 1937 to 1945). What was this magazine? I had no idea but the question and the intrigue helped lead me to a lifelong journey and fascination into pulp and science fiction history over the long years.

|

| "Nick Nack" copy |

Eventually, after decades of comic books, pulps and science fiction, I revisited this book, wanting to really read it in its entirety for the first time, and was transported back to my childhood as I realized that most of the stories here I already knew, burned as they were ... no, better yet, hard wired as they were into my memory. "As Never Was", "The Time Locker", "Farewell to the Master", "The Sands of Time" and others, all recalled and told to me and my brothers in the dark with a flashlight, and all originally published in the Street & Smith science fiction pulp Astounding Stories (or its later name, Astounding Science Fiction)

I also wanted to get a better copy of this book. The duct-taped battered "Nick Nack" copy was fine from a nostalgic family sense, but I wanted a copy that came closer to what it was like when it was originally published. A little research turned up the fact that the book originally possessed a dust jacket and also had several printings.

|

| Random House 1946 original printing listing 35 stories on cover |

The original June 1946 first printing of this thick volume had over 1000 pages, including the five page introduction by the editors, Raymond J. Healy and J. Francis McComas. The designer and cover artist was George Salter. Inside were 35 stories culled primarily from the pages of Street & Smith's Astounding Stories / Astounding Science Fiction. One each hailed from Street & Smith's Unknown, Teck's Amazing Stories and Fiction House's Planet Stories. Here is the full story list, including where they were originally first published:

- Requiem - Robert Heinlen - [Astounding, Jan/40]

- Forgetfulness - Don A. Stuart (John W. Campbell) - [Astounding, June/37]

- Nerves - Lester Del Ray - [Astounding, Sept/42]

- The Sands of Time - P. Schuyler Miller - [Astounding, Apr/37]

- The Proud Robot - Lewis Padgett - [Astounding, Oct/43]

- Black Destroyer - A.E. Van Vogt - [Astounding, July/39]

- Symbiotica - Eric Frank Russell - [Astounding, Oct/43]

- Seeds Of The Dusk - Raymond Z. Gallun - [Astounding, June/38]

- Heavy Planet - Lee Gregor - [Astounding, Aug/39]

- Time Locker - Lewis Padgett - [Astounding, Jan/43]

- The Link - Cleve Cartmill - [Astounding, Aug/42]

- Mechanical Mice - Maurice A. Hugi (ghosted by Eric Frank Russell) - [Astounding, Jan/41]

- V-2: Rocket Cargo Ship - Willy Ley - [Astounding, May/45]

- Adam And No Eve - Alfred Bester - [Astounding, Sept/41]

- Nightfall - Isaac Asimov - [Astounding, Sept/41]

- A Matter Of Size - Harrry Bates - [Astounding, Apr/34]

- As Never Was - P. Schuyler Miller - [Astounding, Jan/44]

- Q. U. R. - Anthony Boucher - [Astounding, Mar/43]

- Who Goes There? - Don A. Stuart (John W. Campbell) - [Astounding, Aug/38]

- The Roads Must Roll - Robert A. Heinlein - [Astounding, June/40]

- Asylum - A.E. Van Vogt - [Astounding, May/42]

- Quietus - Ross Rocklynne - [Astounding, Sept/40]

- The Twonky - Lewis Padgett - [Astounding, Sept/42]

- Time -Travel Happens! - A. M. Phillips - [Unknown, Dec/39]

- Robot's Return - Robert Moore Williams - [Astounding, Sept/38]

- The Blue Giraffe - L. Sprague de Camp - [Astounding, Aug/39]

- Flight Into Darkness - Webb Marlowe - [Astounding, Feb/43]

- The Weapons Shop - A.E. Van Vogt - [Astounding, Dec/42]

- Farewell To The Master - Harry Bates - [Astounding, Oct/40]

- Within The Pyramid - R. DeWitt Miller - [Astounding, Mar/37]

- He Who Shrank - Henry Hasse - [Amazing Stories (Teck Pub.), Aug/36]

- By His Bootstraps - Anson MacDonald (Robert Heinlen) - [Astounding, Oct/41]

- The Star Mouse - Fredric Brown - [Planet Stories (Fiction House), Spring/42]

- Correspondence Course - Raymond F. Jones - [Astounding, Apr/45]

- Brain - S. Fowler Wright - [?, 1932]

The author line-up is science fiction royalty, the stories some of the most respected of the genre. At least two of the above were later turned into films, Harry Bates' Farewell To The Master was the basis for the classic The Day The Earth Stood Still in 1951, while John W. Campbell's (writing as Don A.Stuart) Who Goes There? gave rise to a less stellar The Thing From Another World also in 1951. It makes me wonder whether this anthology played a big part in bringing these great stories to Hollywood's doorstep, as buried as they had been in old pulp magazines, were less likely to be seen and remembered.

The anthology was conceived in 1944 and much credit for the high literary bar set goes to John W. Campbell, the writer/editor of Astounding Stories/Science Fiction who first published most of the stories. Campbell assumed the editorship in late 1937 and his tenure breached what is known as "the golden age of science fiction".

Astounding Stories debuted cover date Jan/30 under the editorship of author Harry Bates and published by Publishers Fiscal Corp, a sub-publisher of Clayton Magazines. It was clearly influenced by Hugo Gernsback's Amazing Stories but was really only a knock-off, trending more towards pulp-ish fiction than harder science. The first 34 issues, ended with Vol 12, #1 (Mar/33). After a hiatus of 7 months the title was bought by Street & Smith and re-launched with Vol 12, #2 (Oct/33) and F. Orlin Tremaine as editor, ushering in a standard of fine literary fiction wrapped around elements of scientific speculation and innovation. These stories would become the gold standard for intelligent science fiction that would be continued in Dec/37 when John W. Campbell became editor (see letter from Campbell to Aug/47 Writer's Digest below), a tenure that would last until Dec/71. The title would change to Astounding Science Fiction in Mar/38 and to Analog Science Fiction/Fact in 1960, continuing to this day.

John W. Campbell's long editorship would shepherd the early careers of some of the giants of the genre, individuals whose influence will be long felt in science fiction. When Martin Goodman launched his science fiction pulp Marvel Science Stories Aug/38, he shakily modeled the editorial slant on Astounding Science Fiction, leaning the content towards intelligent harder science speculative fiction and even launching a letter page "Under the Lens" that was patterned after Astounding's "Brass Tacks".

.jpg) |

| Vol 1, #1 (Aug/38) [Norman Saunders] |

|

| Vol 1, #2 (Nov/38) [Frank R. Paul] |

|

| Vol 1, #3 (Feb/39 [Hans Wesso] |

|

| Vol 1, #4 (Apr-May/39) [Norman Saunders] |

Unfortunately, after only five issues, Goodman's title reverted to a traditional pulp fantasy bordering on shudder-pulp content and readers lost a possible companion magazine, as science fiction held no special place in his eyes. Goodman would just as well cancel it as change it to another redundant western pulp. Goodman also cancelled Marvel's sister publication Dynamic Science Stories after only two issues at this same time of the content changeover.

.jpg) |

| Vol 1, #1 (Feb/39) [Frank R. Paul] |

|

| Vol 1, #2 (Apr/39) [Norman Saunders] |

A sampling of Astounding Stories/Science Fiction, including first below the issue publishing one of my favorite stories of the Random House anthology, P. Schuyler Miller's "As Never Was", the greatest time travel paradox story of all time from the August, 1944 issue.

|

| Vol 1, #1 (Jan/30) [Clayton] |

|

| Vol 12, #1 (Mar/33) [last Clayton] |

|

| Vol 20, #4 (Dec/37) [1st John W. Campbell editor] |

|

| Vol 12, #2 (Oct/33) [1st Street & Smith] |

|

| Vol 22, #1 (Sept/38) |

|

| Vol 23, #5 (July/39) |

|

| Vol 28, #4 (Dec/41) |

|

| Vol 29, #5 (July/42) |

|

| Vol 31, #5 (July/43) |

|

| Vol 33, #2 (Apr/44) |

A second printing of this Random House volume came out in September 1946, which I believe was identical to the first. A third printing came out February 1947. The fourth printing in August 1950 is slightly larger in size and physically thicker, but comes in at only 824 pages, editing out the final 5 stories listed above. The books is substantially thicker due to a better paper stock. A 5th printing followed in August 1951 and a 6th printing in July 1952. I don't know if the second and third printings featured 35 or the shorter 30 stories that the fourth contained..

|

| Random House 1950 printing listing only 30 stories on the cover |

Portions of the book were also released as a paperback in the 1954 by Bantam's Pennant Books, #P44. Only eight stories from the original anthology were included:

- Requiem - Robert Heinlen

- Black Destroyer - A.E. Van Vogt

- Time Locker - Lewis Padgett

- Mechanical Mice - Maurice A. Hugi

- As Never Was - P. Schulyer Miller

- Quietus - Ross Rocklynne

- Robot's Return - Robert Moore Williams

- Farewell To The Master - Harry Bates

Additional ("more") stories were re-published here, Bantam #1310: (contents unknown at this time)

A third here, January 1966 edition. Same contents of the 1954 paperback edition:

This Bantam 1966 edition below ("More") probably has the same 7 story contents of the ("More") Bantam #1310 paperback above:

- The Proud Robot - Lewis Padgett

- Heavy Planet - Lee Gregor

- The Link - Cleeve Cartmill

- Adan and No Eve - Alfred Bester

- Nightfall - Isaac Asimov

- The Roads Must Roll - Robert Heinlein

- Within Thge Pyramid - R. DeWitt Miller

There was also an edition published in 1957 under Random House's Modern Library Giant series, #G-31. This volume has a different cover but reprints the original 35 stories once again, coming in again at over 1000 pages, including a new uncredited 6-page introduction detailing the history of the book's genesis. This edition went through a total of 9 printings up to October 1964.

|

| 3rd Printing : Modern Library Giant #G-31 |

In 1975 Del Rey Books, the new science fiction imprint of Ballantine Books (and owned by Random House) released a softcover version of the original hardcover edition, clocking in at 997 pages, with all of the original 35 stories.

The 1979 printing is below, with all 35 stories.

In 1985 Random House Value Publishing released it again in hard cover, although I don't know what the entire contents are. In actuality, there may even be further permutations of this book that I've missed. If anyone knows of any, please let me know.

Finally, there appears to have been a British version of this book published by Grayson and Grayson in 1952. This edition printed only 11 stories and ran 327 pages. The contents were:

- The Roads Must Roll - Robert A. Heinlein

- Seeds of the Dusk - Raymond Z. Gallun

- Flight Into Darkness - Web Marlowe

- Time Locker - Lewis Padgett

- Mechanical Mice - Maurice A. Hugi

- Adam and No Eve - Alfred Bester

- The Link - Cleve Cartmill

- The Sands of Time - p. Schulyer Miller

- A Matter of Size - Harry Bates

- Nightfall - Isaac Asimov

- The Twonky - Lewis Padgett

I acquired most versions of the book in my quest to unravel its mystery to me. Somehow I even acquired William F. Nolan's copy of the book!!!

Finally I felt I knew all that could be uncovered. That was, until I dove into my research for The Secret History of Marvel Comics.

Finally I felt I knew all that could be uncovered. That was, until I dove into my research for The Secret History of Marvel Comics.

As I pored through decades of Writer's Digest, I was surprised to come across several issues in 1946 where this book was referenced. The first reference was from before the book was even published and I realized that this tome was actually one of the earliest hardcover anthology collections of science fiction stories in history by a "name" American book publisher.

The references were in The Forum, the letter pages of the trade journal and centered around a discussion of royalty payments to the original pulp authors. For months prior to this the letter pages were filled with discussions of "writer's rights" (from an editorial article I do not have) and what policies various pulp houses had in enforcing these "rights" (example, first North American Serial Rights). Pulp editors and authors all chimed in, including Ray Palmer of Ziff-Davis. The back-and-forth is fascinating, and showcased the types of debates that original creators/authors had been fighting with publishers for decades with respect to their just compensation in both the "first" publishing as well as the "reprint" rights as anthology publishing began to rise post-war. A window can also be seen into how the lowest tier of authors were treated, namely these authors in the pulp houses.

I'm going to present these discussions in their original, unedited form. The original letter by author P. Schulyer Miller (referenced just below) I do not have, as it was sent by Miller to Bennett A. Cerf, President of Random House, and forwarded to Writer's Digest by Bennett (and I don't believe actually printed). Miller had 2 stories reprinted in the volume, The Sands of Time and As Never Was.

Since we're dropping into the middle of an already raging letter page controversy, I'm starting with a letter from Ziff-Davis editor, Ray Palmer:

WRITER'S DIGEST January 1946:

Letter from Ray Palmer, editor at Ziff-Davis Publishing:

“Ziff-Davis Pulps Buy First Rights Only”

Sir:

Note the “boys” are making dire predictions as to what’ll happen when the

“reprinters” go back to business. Do they mean they are aiming to rook the

writers as soon as the going gets tough? Nope, I’m not forgetting them days! I

was one of the rooked writers.

My dealing with writers seems to

be strictly personal. The company has never changed its “policy” of buying all

rights it can get. But it also has never changed its policy of sticking by the

deals its editors make. So I guess the writer who deals with me can do it with

confidence.

As for these editors who so

kindly warn me, let’s put it this way – which one of ‘em’s going to be the first to put out one of those reprints?

Ray Palmer,

185

North Wabash Avenue

Chicago

1, Illinois.

WRITER'S DIGEST May 1946:

Letter from Bennett A. Cerf, President, Random House, followed by a comment from Writer's Digest editor Richard K. Abbott.

Sir:

I am forwarding Mr. P. Schulyer

Miller’s letter regarding payments for permission to use stories in our new

science fiction anthology to Mr. Ray

Healy, who is editor of the book and who made all the necessary

arrangements therefor. You will hear very promptly from Mr. Healy in regard to this matter.

I would like to say a word in

general about our policy with regard to stories used in Random House and Modern

Library anthologies. Having published many anthologies and having edited a

goodly number into the bargain, my interest in this subject is as great

probably as that of anybody in the business, and is most certainly my intention

to see that the authors represented in these anthologies get their full share

of the spoils.

I do not think that it is possible to make any hard and fast rule

that will govern anthology payments. For example, an editor who comes to a

publisher with an ingenious anthology idea is certainly entitled to more than

one who accepts a specified job that originated in the publisher’s mind.

Furthermore, the question of possible profit must be considered. If it’s a

whopping big anthology to be sold at bargain price, the profit margin obviously

is small and the editor or publisher can’t possibly pay as much for his

material as he can on a smaller volume aimed at the higher priced market.

Until

recently it was almost the universal rule, as you know, for editors to buy

anthology material outright. The price paid

for such material has risen steadily in the past several years and in many

instances authors have gotten $50 or more for the use of a story that has

already been used in a dozen other collections.

This raises another point: does a story that

is being anthologized for the first time deserve a higher payment than one that

has become hackneyed through endless repetition?

The idea of cutting original

authors into royalties on anthologies is comparatively new. In general, I

consider it the fairest basis for operation. If the anthology is the editor’s

own idea, I think the said editor is entitled to 50 percent of the regular

royalty rate, with the other 50 percent being divided on a pro rata basis among

the authors included. If the publisher gets the idea, I think the editor should

get a maximum of 25 percent reserved for division among the authors.

To

sum up, I don’t think the time has arrived yet when the publisher can make a

hard and fast rule that will govern all the anthologies on his list. The

special considerations simply must be taken into account. On the whole, I think

publishers in America are fully aware of their responsibilities in this

anthology question and are sincerely interested in being fair to everybody

concerned. Incidentally, I’d like to say in conclusion that in my opinion this

whole anthology business hs been overdone to an almost ludicrous degree. I think it will be a fine thing for the whole

publishing business is a moratorium on all new anthologies is declared for the

next five years.

Bennett A. Cerf, President,

Random House,

20

East 57th St.,

N.Y.C.

22, N.Y.

- RANDOM

HOUSE is bringing out an anthology of science fiction and several of our

readers who are included in it want to know about payment. In some cases,

the science fiction story was published first by pulp houses who owned all

rights. Should RANDOM HOUSE pay the pulp publisher a fee and let it up to

the pulp paper to retain the entire amount, or should RANDOM HOUSE go out

of their way to see that the author gets his payment even if the pulp

house holds on to it? We don’t know what any other book publisher would

do, but RANDOM HOUSE, on the basis of its past, will do the big thing.

It’s just another point showing how the pulp publisher who buys all rights

can, IF HE WANTS TO, play hell with the writer. –Editor.

WRITER'S DIGEST June 1946:

Letter from Raymond J. Healy, co-editor of Adventures In Time And Space, followed by a comment from Writer's Digest editor Richard K. Abbott.

Sir:

Bennett Cerf forwarded your

letter about the matter of pulp authors’ rights in the anthology field; also a

copy of your article in the October 1945 Digest

concerning rights in general. The idea for a Science-Fiction anthology was

original with me and, along with my associate, J. Francis McComas who has had pulp stuff published under the pen

name of Webb Marlowe, I spent over

two years plowing through fifteen years’ issues of the various magazines in the

field.

We accepted the usual anthology

contract from Random House and

agreed to complicate our task as editors further by handling and acquiring the

necessary permissions. This is a routine way of doing things amongst

anthologists. But it is a complicated, difficult and laborious task as anyone

with experience in the field will agree.

We wrote letters, sent cables

and telegrams, interviewed writers personally and spent so much time and money

in the process that our book will have to do very well indeed to compensate us

properly for the efforts expended.

We agreed to pay Street and Smith a half cent a word for

the stories they control and offered the same rate to writers who had control

of their own material. A fifty percent cut over the original sum the writers

received for their stories is certainly not unfair – it might very well mean

more that they should receive had they accepted a royalty agreement – but that

is, of course, purely speculative. Actually, the idea of royalty did not occur

to us before seeking permissions although since the completion of our collection

we have talked with a number of prominent writers about just that subject.

Among those staunchly supporting this “share

the wealth” (if any) campaign were Anthony

Boucher, Cleve Cartmill, A.E. Van Voght, Craig Rice, Robert A.

Heinlein, and a number of other top-notch boys not necessarily familiar to

or with the pulp field, such as Frank

Fenton, Jo Pagano, John Fantey Bezerides, all novelists

who have no such problems about reprint rights.

These latter fellows heatedly

discussed still another problem of writers failing to share in a just

apportionment of the income their works provide and that is the income

circulating libraries enjoy from their books.

Take for example, a good but not

too successful mystery novelist. A bookstore will pay anywhere from a dollar

twenty to a dollar fifty for his new book. It is usually placed in the rental

library where it may not even pay for itself but where again it may earn as

much as five dollars for the bookseller. The author has received perhaps a quarter

as a royalty from the publisher. Where is the equity?

But to get back to our mutton: Mr. Ralston at Street and Smith did at one time in our negotiations suggest that

we offer a regular book royalty contract so that the authors might benefit more

fully from the publication of our book. It seemed to McComas and myself that if our collection did make any money for Random House, who were gambling heavily

in contracting to reprint a quarter of a million words or so in a field that

until that time had been successful commercially only in the pulps, it would be

fine. But we could not see saddling them with an almost impossible job of

bookkeeping and what is more – and perhaps more to the point – we were anxious

to make a few dollars for ourselves for the long and difficult job of culling

we had undertaken. We followed what we assumed to be a fair practice inasmuch

as we agreed to pay the first permission rate quoted to us. It was also our

understanding that Street and Smith

intended to turn over the fees, or a goodly share thereof, that they received

from us to the authors whose stories we requested to reprint.

P. Schuyler Miller seems like a nice and progressive fellow, but he

is wrong in suggesting that editors contact writers directly at first. Before

that can be done, publishers will have to change the copyright clauses that

appear in all books and magazines. We secured permission to reprint his second

story from Street and Smith who owns

the rights to it and presume they will reimburse him for it because of the

attitude shown in our correspondence with them, referred to above.

Mr. Ralston, although heartily favoring a royalty contract for his

writers, agreed to the half cent a word arrangement originally suggested

because he was broad-minded enough to admit that the book, although perhaps

more profitable for the authors included, were they to receive royalties, might

very well be unprofitable to the editors and publishers.

Under the present arrangement,

the book will see the light of print, the authors will be widely publicized

under the imprint of a distinguished, top-flight book publisher, and I think

that except for theory, everyone will be happy.

I have had letters from a number

of writers included in our anthology – it is to be called “Adventure in Time and Space”

incidentally – who were absolutely delighted with the rate we were offering for

stories they had forgotten for years. I really don’t think McComas and I have been villains or even mildly greedy. We embarked

on our venture to make a few dollars for ourselves and still hope we may.

We are inclined to agree with Mr. Cerf that the whole anthology field

has been overplayed of late and in the future will probably let somebody else

worry over the ethics involved in the compilation of such properties.

Raymond J. Healy,

117

Gretna Green Way,

West

Los Angeles, Calif.

- What

this whole thing boils down to is this: Random House is owned and run by square shooting people. Over

a period of years, free-lance writers are far better off because Random House exists than they

would be if there were no Random

House; and so is American literature. On a specific deal like this

one, it seems to us though the free-lance writer who sold a stf story for $40 and receives a

$20 bonus because it is reprinted in an anthology can’t buy much bread on

that kind of business. We would have suggested, on this kind of book which

plumbs ground hitherto 100% ignored, that a flat check of $50 would have

been The Thing To Do because it would set a higher standard for the next

fellow and anything that makes it tougher for the next publisher makes it

better for high caliber firms like Random

House.

- (If

the big pulp houses would agree to a base minimum NOW of 2½c a word for

all pulp fiction they buy it would be the biggest single factor in keeping

out of their pie the sleazy, cheesy, shyster beat-the-printer,

beat-the-writer two-bit pulp publisher who will march on this section of

the publishing business in 1952 just as he did in 1932. Keep the rascals

out by erecting a high word-rate barrier.)

- We

agree that if Random House had

paid $50 flat for each story it would have been the sort of unselfish act

one is always asking the other fellow to do. In addition, Random House does its share of

these things, we learn from our readers.

- Editor

Healy

didn’t do the far reaching Big Thing, but he did the commercial fair

thing. – Editor.

As an aside, the May/46 issue below also carried a note that Random House was set at that moment to move into the building in back of St. Patrick's Cathedral:

"The trend of the month has been toward much enlarged quarters – buy or build – by all types of publishers to allow for their enlarged production plans. This has involved purchase of entire office buildings by several publishers, as Random House recently bought the elaborate house back of St. Patrick’s Cathedral at 457 Madison Avenue. Their move from 57th Street is due about May first."

WRITER'S DIGEST July 1946:

Letter from sci-fi author Ross Rockylynne (Ross Louis Rocklin):

Sir:

Back to the stf anthologies again:

I had thought Street & Smith

would speak up in these columns and explain their stand on the matter. They

accepted a half-cent a word on all stories to which they owned book rights,

then turned around and gave every cent of this money to the authors of the

stories. At least this was true for the stf anthology put out by Crown Publishers, “The Best of Science Fiction.”

In effect, Street & Smith acted as authors’ agent, without collecting the

usual 10% … although they will collect good will and a certain amount of

publicity.

Moreover, S&S brought more

brains to bear on the deal than could be expected from most authors; the book

rights to these stories revert back to S&S after six months, when they may

be bought again.

Did other companies act as

fairly in this matter? I don’t know. But I am assured by John W. Campbell, Jr., the old atom expert who controls the orbit

of Astounding

Science Fiction, that S&S intends to act similarly for stories they

own which will be published in the long-heralded McComas and Healy

collection, Adventures in Space and Time. I don’t think our archeologist

friend P. Schuyler Miller will have

to dig very deep for fair treatment …

Whatever the inequities of the

situation may be, S&S deserves a round of applause for the way they handled

their end. Of course, we would prefer that S&S turn over all rights to us

battened-upon-the-brain-squeezers, but that’s another long (and so-o-o weary!)

story.

As for the suggestion of a flat

$50 rate – whoa! – back up! Some of these anthologized yarns run 20,000 words!

Let’s keep it as to word-length, huh? –unless someone can (as I prefer) produce

an equitable method of distributing royalties which will allow the authors to

gamble on the success of the books.

Ross Rocklynne,

4122

Toluca Lake Avenue.

Burbank,

California

WRITER'S DIGEST July 1946:

Letter from Henry Steeger, President of Popular Publications:

Sir:

In answer to a query from your

reader, of course we would pay for any of the pulp paper stories from the Popular chain. Should the editors wish

to reprint them in our new Story Digest.

The authors would be paid at the same rate as though their stories had been

published in any magazine outside of Popular

Publications. I am sending you a bomb under separate cover for even

inferring that we might undertake such an underhanded practice as to pay less

for stories reprinted from our own magazines.

The entire selection of material

for Story Digest is made by the

editors, but they will be very glad at all times to have suggestions from

authors as to stories they might like to see included.

Payment is at the rate of $75

for stories taken from pulp paper magazines, and $75, $100 and $150 for stories

from all other publications, depending upon length. Payment is on acceptance.

At the present time we are not using any original material.

Henry Steeger, President,

Popular Publications,

205

East 42nd Street, New York 17.

WRITER'S DIGEST July 1946:

Letter from sci-fi author P. Schuyler Miller:

Sir:

Having, as yet, had no evidence that my subscription is again active,

other than the highly entertaining little manual on how not to plot, I picked

up the May Digest on a newsstand and

was at once confronted by Bennett Cerf’s

comment on my letter, with regard to Random House’s science-fiction anthology

and the “all rights” situation.

May I emphasize that I have no

quarrel at all with Mr. Cerf, for

whom I have the utmost respect as a publisher and columnist – and I have no

evidence that I have any reason to quarrel with the editors of the anthology in

question, Messers Healy and McComas. If the terms they offered for

the one story on which I do own book rights – ½c a word flat payment – hadn’t

been satisfactory, I could always have tried to dicker or refused outright to

assign permission to use the story.

I was trying to bring out the completely

screwy complications of ethics (if you want to call it that) which arise from

the policy of pulp publishers of buying all rights. Three stories of mine,

published by the same publisher over the last nine years, are chosen for two

anthologies. For one (one which the publisher had bought “all serial rights”) I

will be paid on the terms agreed upon with Mr. Healy. For a second in the same anthology, Street & Smith will be paid (presumably at the same rate,

unless they struck a better bargain). For the third, Street & Smith have willingly reassigned clothbound book

rights, without asking for any share of the payment. Same publisher, same author,

and in two of the three cases, same anthology. It’s the formula that is to

blame, not what happens when you use it.

Street & Smith assigned book rights to the third story to me

because the editor of the collection in which it will be used, August Derleth, happened to know where

I am and asked me to ask for assignment. Whether he does that in every case I

don’t know, but I would not be surprised to find that he does, because he knows

the fantasy field and its writers, inside out and is in a position to write

directly to the people whose work he wants to use.

Healy and McComas, I

should imagine, are in a very different position – more or less, novices in the

field, having decided what stories they want and taking the most direct way to

get them. If I had had their idea first, and had done anything about it, I

would probably have done what they seem to have done – namely written to the

original publisher of each story to find out who owns book rights. It might

have taken months to run down each individual author, without the inside track

a man like Derleth has. Street & Smith happened to own

rights to one of the two Miller

yarns they wanted – so S&S sold them. They didn’t own book rights to the

other, so Healy was referred to me. All straightforward.

I like Mr. Cerf’s idea of a pro-rated royalty, and have an article anthologized

on that basis. If sales are small, this plan may bring the author less than an

outright sale to the editor.

Actually, much of the inequity in the

situation would be alleviated if magazine publishers who buy “all rights” will,

after some lapse of time which seems reasonable, automatically reassign book

and other rights to the authors – or if they will give an author a blanket

assignment of such rights to all his stories they may have published*. Then anyone with hope or faith in

sales possibilities can set out to do something about book publication, or

radio or film use. As it is, such rights are assigned to the author only for a

definite purpose – not on contingency.

To answer the questions you

raise in your own comment on Mr. Cerf’s

letter: I really doubt any publisher, or even the average editor, can afford to

go out of his way to insist that the author and not not the pulp publisher is

paid for book rights to an anthologized short story. Novels are another matter.

And your last sentence sums the whole substance of both my letters.

P. Schuyler Miller,

108

Union Street,

Schenectady

5, N.Y.

This July issue also sports a 10 page article on the general topic of “Your

Book Reprint Rights” by Harriet A.

Bradfield. Included are all the available markets including the rise of the burgeoning paperback reprint houses, book-digest reprint lines, magazines with book features and the syndicates. For the first time in cheap newsstand publishing, the inequity of the topic of "reprints" is finally being addressed.

And finally, although not dealing with the Random House anthology or reprint "rights", the August 1947 issue of Writer's Digest has a letter from Astounding Science Fiction editor John W. Campbell, Jr. about what he's looking for in prospective writers. and how specialized the editorial policy is for prospective writers....

WRITER'S DIGEST August 1947:

Letter from sci-fi author and editor of Astounding Science Fiction John W. Campbell. Jr. :

Sir,

The primary comment I can make from the writer's point of view is that to date we have not bought any story whatsoever from anyone who has not read the magazine. Science Fiction is a specialist's field. Within that field Astounding Science Fiction is a specialized magazine. Unless the would be author understands the philosophy of science fiction and the basic editorial concept of Astounding, his chance of making a sale is about as remote as his chance of flipping a coin and have it stand on edge. Possible but not probable.

John W. Campbell, Jr., Editor,

Street & Smith Publications,

122 East 42nd Street, New York 17, N.Y.

Sir,

The primary comment I can make from the writer's point of view is that to date we have not bought any story whatsoever from anyone who has not read the magazine. Science Fiction is a specialist's field. Within that field Astounding Science Fiction is a specialized magazine. Unless the would be author understands the philosophy of science fiction and the basic editorial concept of Astounding, his chance of making a sale is about as remote as his chance of flipping a coin and have it stand on edge. Possible but not probable.

John W. Campbell, Jr., Editor,

Street & Smith Publications,

122 East 42nd Street, New York 17, N.Y.

POSTSCRIPT:

My parents retired 20 years ago and moved their residence out of Queens, New York up into the Adirondacks, in the northern part of Lake George. In January of 2007 they received a phone call from the next door neighbor of Nick Nack. He had passed away at the age of 87 on the 17th and previously left instructions for the neighbor to contact my father for him to avail himself of all Nick Nack's worldly goods, as he had no real family to speak of. I drove down to Forest Hills for my father and all I retrieved were his music albums and books, packing up hundreds of jazz records from the 1940's through 1960's and a score of vintage film books, all loaded in crates. I also took an old yellow manila folder I found stuck between the albums. As I left, I took a photo of his door, knowing the name plate would shortly be removed and no further evidence of Nick Nack ever having lived there for over 40 years would exist, the man who was a disembodied voice on the phone with my father for most of my entire life from age 5 to 50.

When I got home that night I left everything in my garage except for the books and the envelope. I dusted off the books, paging through coffee table books about the great film studios and jazz personalities, interestingly coming across annotated copies of Hollywood Babylon and Jazz Anecdotes where whole paragraphs were underlined, highlighted or cross-out in pencil with the words "wrong" or "didn't happen that way" written in the margins, including the frequent phrase "I was there that night ... not true".

I also opened the envelope, finding a stash of vintage studio publicity photos of jazz musicians, all autographed to Nick Nack. On the top of the pile were vintage autographed photos of jazz greats Bill Evans, Billy Taylor, Mary Lou Williams and Marion McPartland. At the bottom of the pile was a signed publicity photo of my father!

I wonder if Nick Nack ever wanted that book back.

|

| Marion McPartland |

|

| my father, Michael D. Vassallo (circa 1960) |

POSTSCRIPT #2 (5/5/21)

Cleaning out 60 years of accumulated books and magazines in my parents old basement, I came across a partial remnant of that old catty-corner mirrored bookcase mentioned way at the top of this blog post!

This is the very top of the shelf, the "tier, if you will, as the shelf stood like the Empire State building, getting narrower as it rose to the top shelf, in the corner of the room. Ignore the violin bow on top, and what looks like a dinosaur egg on the stool behind it!

SELECTED SOURCES:

- http://www.pulpmags.org/database_pages/astounding_stories.html

- http://www.philsp.com/mags/analog.html

- Adventures in Time and Space: An Anthology of Modern Science Fiction Stories (introduction to 1946 edition by editors Raymond J. Healy and J. Francis McComas )

- Adventures in Time and Space: An Anthology of Modern Science Fiction Stories (introduction to 1957 Modern Library Giant G-31 edition by unknown)

- Writer's Digest, January 1946

- Writer's Digest, June 1946

- Writer's Digest, July 1946

- Writer's Digest, August 1947

- Collection of Michael J. Vassallo

- Collection of Seymour D. Nachamis (the "Nick Nack" collection)