Rather than edit the last post to keep all the "Timely editorial" material in one place, thereby short-changing the Complete Mystery content, I've decided to just re-use the pertinent material here and my apologies to regular followers of this blog for the redundancy. I've split this post into two parts and posted them in reverse order so they flow from part one to part two smoothly and will always load that way in the future.

A full accounting of the censorship battle faced by the comic book industry is a topic worthy of a full

book, and that book has already been written, David Hajdu's The Ten-Cent Plague, the most complete look at the medium's battle with the forces of censorship. What follows below is a condensed, surface-skimming Timely-slanted overview written without referencing Hajdu's book. I wanted to address the material completely from my own perspective. There is no deep analysis here, no discussions of profound cultural significance. Instead I went to all the source articles mentioned below in the text of my post and have just placed it "out here".

I am not going to cover everything on the subject, although I will touch upon most, and will spend time on some aspects and gloss over others. Some/most of the below have been seen and written about before but I also hope I've posted some things rarely or quite possibly never seen before. As always, comments and corrections are encouraged and welcome.

All of the newspaper material was accessed by way of historian Barry Pearl's extensive personal collection of original articles. My undying thanks for being able to access such an invaluable resource. The rest came from my own collection and a handful of other sources. Additional thanks must go out to Rodrigo Baeza, Ray Bottorff, Jr. and Steven E. Mitchell, researchers who've written extensively on the history of comic books and/or censorship and need to be acknowledged. Mitchell's series of articles in The Comics Buyer's Guide in 2003 and 2004 were a seminal look at the history of comic book censorship. Please see the end of "part 2" for a full listing of sources and a bibliography.

Popular culture has a long history of stirring up concerns and triggering the response of attempted

censorship. From comic strips and dime novels to pulps, music and film, all at one time or another would

come under siege from forces that blamed them for all the ills of the world, particularly the dual concerns

of loose morals and violence.

Prelude: What's Old Is New

Before I delve into the subject at hand, I want to shed some light onto the dim past and the mindset of both the Restoration period of King Charles ll and 19th century Victorian England, where ideas and concerns mirrored what we will see in our mid 20th century.

The very earliest reference I've

ever come across concerning the fears that popular culture was corrupting the youth of the day was discovered accidentally in my copy of the April 5, 1739 edition of

The Edinburgh Evening Courant.

On page 3 is a notice relating a bill wafting through Parliament allowing the prohibition of "plays" which "withdraws the minds of the youth from feverer (sic) studies, and corrupt their morals."

The money quote cropped out.......

Given the inordinate amount of stage productions and dramatic history during the Elizabethan period by authors lead by William Shakespeare, Christopher Marlowe and Ben Jonson, it rings rather inexplicable that a century later complaints about "extraordinary pleasure" of the "young and the gay" would require an actual legal maneuver.

The later 19th century periodical publishing aspect I spoke of is not comic books, but the entire parallel genre of children's literature which came of age in the Victorian era and where the preoccupation with childhood manifested itself in the books and magazines produced for the young. As more and more children of the middle class joined the upper class in reading, prominent literary critics of the time played leading roles as arbiters of taste and morality, especially against what was deemed the lowest rung of printed reading matter, the

penny dreadfuls, the reading entity of the working class.

What follows are quotations and commentary from authorities of the day from a wide variety of sources. The similar thread running through all of them is obvious.

The "elite" journals of the time strongly advised parents to supervise the reading "of the rising generation during its first and formative literary experience"(a). The men and women who commented on children's books were convinced that the first books a boy or girl encountered imprinted an indelible pattern to which all subsequent ideas and impressions about the world would conform. The moral welfare of the rising generation seemed poised in the balance and they opposed the unscrupulous publishers exploiting the juvenile market with unwholesome pulp literature. Sound familiar? Further, "individuals who have taken to writing such children's books did so solely because they found themselves incapable of writing any other, and who have no scruples in coming forward in a line of literature which, to their view, presupposes the very lowest estimate of their own abilities"(b).

Critics delved back to old fairy tales and folk stories to retrieve the kind of stimulation they felt the children needed as new attitudes to children found closest affinity with the oldest traditions (c). Charles Dickens spoke for many of his contemporaries when he insisted that "in a utilitarian age, of all other times, it is a matter of grave importance that the fairy tales should be respected"(d). The resurgence of interest in folklore was fueled, in part, by the desire of adults to escape from the social and political reality of an age of doubt and insecurity to an imaginary world where universal human values and natural justice ordered existence(e). The mid-Victorian parent saw childhood as a fleeting period of innocence in a bustling, materialistic world and took pains to shelter this innocence. hence, the choice of suitable reading material being a duty for parents and intelligent observers were acutely sensitive to the formative influence of childhood readings as publishers unleashed "new and pressing dangers to the immature sensibility"(f).

In the 1850's the so-called "gutter press" began more and more to converge on the juvenile market and amassed fortunes by milling out tales of adventure and sensation in penny weeklies, with periodicals that closely resembled the bloods and pennyworths of crime they themselves had published in the 1840's. They attempted to disarm the watch-dogs of juvenile morality. James Greenwood, in "Penny Packets of Poison", fulminated against the dreadfuls, to his mind, the certain cause of the moral ruin and criminality of juvenile delinquents(g). What offended critics most was such stories' challenge of the status quo and the precocious independence and potency of the boy's heroes. They were an uncomfortable contradiction to the romantic and nostalgic images of childhood purity and innocence (h). Said Edward Salmon, an early specialist in children's literature, "they will deprive reading of the great danger which it possesses for the young"(i). Salmon even advocated censorship to check the spread and "pernicious influence" of cheap novelettes and weeklies (j).

Alexander Strahan did not believe censorship would work and his solution was to provide entertaining yet healthy alternatives. In 1869 he introduced "Good Words for the Young", and promised "such literature will not ignoble interest nor frivolously amuse, but convey the wisest instruction in the pleasantest manner"(k). Meanwhile, the creators of "high class" children's magazines were unwilling to adopt the popular formula that earned huge sales for mass-produced papers. They aspired to uplift juvenile taste and to create a demand for wholesome entertainment (l). Most felt that good magazines, even more than good books, "were the most effectual means of holding the ground against hurtful publications"(m).

Juliana Ewing revealed the editor's attitudes: "There is a certain tone of highmindedness and refinement in which the fast rising generation seem to me hardly the equals of the preceding one. I lay a good deal of the blame for this on cheap and nasty literature"(n). Rev. J. Erskine Clark, owner and editor of Chatterbox, observed first-hand the reading habits of poor boys and girls. His major goal was "to oust the insidious 'blood and thunder' of cheap sensational papers"(o).

Other publications like Little Folks achieved a winning balance without succumbing to the sensational tactics of penny thrillers. It was one of the few children's magazines which "at all approach in beauty and general merit the American St. Nicholas or Harper's Young People" (p). Edward Salmon observed, "Boys gain most of their information, apart from what they are taught at school, from the stories that they read. This fact lends a new responsibility to the fiction which is produced for them"(q).

|

|

LITTLE FOLKS c.1885 (Cassell and Company)

|

More :

"Considering the tremendous influence Victorians attributed to early childhood reading, the anxiety occasioned by an influx of shoddy sensational literature conveying 'false visions of the world' is not surprising"(r).

"The early magazine producers aimed to refine the literary tastes of upper and middle class children and to defend them from low standards of art and morality"(s).

"The mind becomes satisfied with a very low standard of art, and a very physical species of pleasurable excitement, and is perfectly content never to look into a book for any higher pleasure(t).

"The Boy's Own Paper achieved phenomenal success in fighting the dreadfuls by imitating their appearance, format and even typeset, to lure "blood and thunder" addicts, but substituted healthy, robust tales for the manufactured rubbish of sensational weeklies"(u).

The point of all of the above is to show and record a crucial era in attitudes to children, reading and children's literature in the Victorian era. As we move across the pond to the United States, while our puritanical standards would likewise rear up to shout down literature deemed "inappropriate", there was a much larger middle and lower class and a smaller "cultural elite" calling the shots on a population consisting, even more so by the end of the century, primarily of diverse immigrant backgrounds. Cheap publications like those spearheaded by Street and Smith starting in the 1850's would provide adventurous respites for children. Tip Top Weekly debuted America's first continuing fiction hero, Burt L. Standish's Frank Merriwell and others would follow suit as comic strips, comic booklets, dime novels, pulps and eventually comic books (as we know them), provided the middle and lower classes with cheap, sensationalist reading material.

But as we saw in Victorian England, what's old is new, and our medium of choice would have the same trouble.....

After early published criticisms in the first decade of the new century, in 1911, the editor-in-chief of

Collier’s Weekly spoke at a mass meeting of the “League for the Improvement of the Children’s Comic

Supplement” to lambaste newspaper Sunday comic supplements as “vulgar” and “offensive and harmful

to the minds of children”, offering up the New York Times’ Photographic Supplement as the shining

example of “beautiful, interesting and timely” material for their readers.

|

|

The New York Times (1911)

|

From a comic book

perspective, the very earliest attack against the medium came on May 8, 1940, when

Sterling North, the literary editor of the

Chicago Daily News, railed against the nascent comic book as a

“threat” and

“a poisonous mushroom growth.”

|

| Chicago Daily News (May 8, 1940) |

The war years that followed yielded complaints in magazines and newspapers including the

Chicago Tribune in 1943 and the

Southtown Economist in 1945, but the country was more importantly occupied with the war effort to pay them much notice. Plus, comic books by the hundreds of thousands were being shipped overseas to our servicemen to help with morale.

|

|

CHICAGO TRIBUNE January 19, 1943

|

|

|

Southtown Economist, April 1, 1945

|

In 1944, the rising permutations of newsstand comics began to draw the ire of the Catechetical Guild (St. Paul Minnesota) and they published an eight page pamphlet titled The Case Against the Comics by Gabriel Lynn that warned parents about the damage being done to children by the types of comics which "failed to meet the standard of good recreational reading". It wasn't a wholesale condemnation of comics per se, just of the "bad ones", which were most of them!

|

|

1944 (The Catechetical Guild)

|

By1947, the anti-comics mood reared its head again and this coincides exactly with the post-war decline in superhero comics and the rise of genre comics, specifically "crime" comics, a genre that gave more "bite" to the reader than the by now almost "quaint" superhero comics. The post-war reader was not as innocent any longer and entertainment reflected that harder edge be it crime comics, pulp novels, radio shows or noir films.

1947 is also the year that crime comic books began to increase in number across the newsstands, building on Lev Gleason’s earlier groundwork. In 1942 publisher Lev Gleason successfully renamed his Silver Streak Comics title into Crime Does Not Pay, introducing the crime anthology comic book with artists including Charles Biro and Bob Wood. Although lost amidst the sea of war era superhero comics, by the post-war years sales surged. This did not go unnoticed at Timely, where in the spring of 1947 publisher Martin Goodman instructed editor-in-chief Stan Lee to delve into the genre and the result was Justice Comics and Official True Crime Cases, both cover-dated Fall 1947 and sporting action-packed Syd Shores covers, fresh from his duties on Captain America Comics. Five more titles would follow the following year.

In early 1948 the comic book industry got a stirring out of some of the public. The New York Times ran an article on February 4, 1948 explaining that comic book publishers had received a city warning about cleaning up their content:

Then in March of 1948, all hell began to break loose. Enter Fredric Wertham. Dr. Fredric Wertham was a Bellevue Hospital psychiatrist with impeccable credentials, a champion of “social psychiatry” dealing with the needs of the poor and minorities. Born in Bavaria, Germany in 1895 (as Frederic I. Wertheimer) and earning a degree in medicine, he came to the United States in 1922 to work in the Phipps Psychiatric Clinic of Johns Hopkins Hospital. In 1932 he was the senior psychiatrist at Bellevue. In 1941 he wrote Dark Legend, A Study in Murder, a case study of a 17 year old boy who killed his mother, and in 1944 (some sources say 1946) he opened the LaFargue Clinic in Harlem, the first clinic to specialize in the treatment of African-Americans with psychiatric illness and therefore came into contact with scores and scores of disturbed children, children both deemed juvenile delinquents and those seriously (diagnosed by 1940's standards) mentally ill. Wertham became the most important critic of the impact on children by the mass media, and by extension, comic books.

Three major events got the ball rolling. On March 19, 1948, Wertham sponsored a symposium under the ongoing professional umbrella of the Association for the Advancement of Psychotherapy. Four top professionals presented and read papers with the introduction by Dr. Frederic Wertham himself, "The Psychopathology of Comic Books". Wertham immediately would expound on his ideas in the March 27, 1948 issue of Collier's Weekly and the May 29, 1948 issue of The Saturday Review of Literature, both to be covered below.

The actual minutes of the symposium were published in the July, 1948 issue of the American Journal of Psychotherapy, a quarterly publication that was the official organ of the Association for the Advancement of Psychotherapy. This journal covered the proceedings of the Association's meetings as well as editorials, case studies, book listings and advertisements dealing with all areas of psychiatry and psychology. The journal was released after this firestorm ensued.

Here are the chapter heading pages:

After a brief introduction by the symposium's sponsor (Wertham), four professionals presented :

1) "The Comic Books and the Public" by Gershon Legman (1917-1999)

Legman's logic is so twisted that after laying out the newsstand's product of violent crime comic books (obviously skewing Lev Gleason's crime titles and downplaying the importance of their end-of-story "crime does not pay" moral), he then trashes "educational" and "classic" comics (a thinly veiled reference to the Classics Illustrated line), as worse than the ultra violent crime comics they were meant to improve upon, as well as being even more harmful. The formulaic complaint of Superman's "force of might" and the stunningly ridiculous comparison of Superman's effect on an American child being worse than a Nazi's effect on a German child is so far-fetched from common sense as to make me wonder about the state of academia of the late 1940's.

Legman also complains about Antisemitism in the comics without realizing that the vast preponderance of the creators of the time were in fact Jewish. But the real gist of Legman's spiel is finally revealed if you read closely. He wonders whether "the fixation on violence and death in mass-produced comic books is a substitution for a censored "sexuality" or "intended to siphon off the aggression felt against general societal conditions". Legman would the next year publish the book Love and Death, which was an attack on sexual censorship, and ultimately be a pioneer in the serious study of eroticism in folklore. In retrospect, this puts his 1948 views into perspective

2) "Aggression and Violence in Fantasy and Fact" by Hilde L. Mosse, M.D. (1913-1982)

Dr. Mosse expounds on the claim that comic books provide an outlet for a child's innate "aggressiveness". First she goes into a discussion about Sigmund Freud's theory of the "death instinct", an instinct she believes comic books play on. As opposed to a "life instinct", the "death instinct" needs an outlet and is a powerful obstacle to culture, explaining all forms of violence from wars to discrimination, cruelty and exploitation. According to Dr. Mosse, "aggression" is a state of readiness to commit an act of cruelty and cause pain in others/oneself, and that aggression comes from "frustration", which is then channeled towards "fantasy" and stimulated by "desire" or "wish fulfillment".

Throw in comic books and puberty and you have a volatile mixture of violence and sexual fantasy requiring an outlet! The bottom line, according to Dr. Mosse, is that comic books are hindering a child's chance at normal development.

Dr. Hilde L. Mosse was one of the founder's (with Wertham) of the LaFargue Clinic in Harlem. Her background is a perfect explanation for her views on children and violence. From a rich and prominent German Jewish family, her exposure to the horrors of the Nazi's rise to power, causing her family's flight from Germany, is a fascinating story that can be read here:

3) "The Child's Conflict about Comic Books" by Paula Elkisch, Ph.D

Dr. Elkisch's approach was to go directly to the children and find what their reactions were to comic books. After evaluating an exhaustive look at various studies, questions and reactions were collated, comparing comic books to "pleasure books (regular, non-comic books). The standout point of the "objectionable" type of comic book was that they "motivated dangerous imitation" (mimicry). Therefore, children will imitate to fit in and be like "those in authority who have the power". More terms like "imitation being a defensive mechanism" and "the process of identification and its role in the formation of the ego and superego" are mentioned, but the basic thrust is the concept of "identification with the aggressor". More nonsense on the awareness of the pleasure causing "guilt" and the fact that comic books appeal to the "primitiveness" of the child, as well as "the reading of picture language is (according to Freud) only a very incomplete form of being conscious".

Gosh! How did we ever survive childhood??

Paula Elkisch was a psychoanalyst specializing in child psychiatry. There are extensive collections of her papers at The Center for Jewish History. The bulk of the collection consists of off-prints of her articles on child psychiatry, published in Germany and after 1940 in the United States, as well as her collection of off-prints by the psychoanalyst Kurt Robert Eissler, who published extensively on Sigmund Freud. Also included are photocopies of her poetry and other writings as well as copies of correspondence with Thomas Mann. Here is a link to the collection:

4) "The Practical Aspects of the Bad Influences of Comic Books" by Marvin L. Blumberg, M.D. (1915-1995)

Child Psychiatrist Marvin Blumberg wrote that comic books "awaken the sado-masochism which lies dormant in children". Partially blaming "the increased pace and tensions of living", Dr. Blumberg relates that "the juvenile group of the population is rapidly becoming infected with the neuroses of the adult rulers", and that "neurotic and emotionally deprived children (the most prolific comic book readers) are most suggestible to be influenced by comic books".

Dr. Blumberg was a pediatrician and a psychiatrist and president of the Association for the Advancement of Psychotherapy and a past chairman of the Department of Pediatrics at The Jamaica Hospital in Queens, NY.

A discussion then followed the presentation. Johann G. Averbach, M.D. blended "forbidden tendencies" with "bloodthirsty and sexy comic books" and compared comic books with fairy tales, concluding that "the fantastic elements of fairy tales depicts a world far removed from reality", therefore it doesn't harm a child. The last comparison was to Pavlov's dog, "where aggression and sexual desire are stimulated by the presentation of comic book pictures".

At the very end, comic book names we recognize presented comments. How these individuals became involved with the symposium is unknown to me.

Mr. Charles Biro, identified as "an editor of comic books", stated vigorously "that comic books are getting better". Biro was an editor, writer and artist at that time for Lev Gleason's line of crime comics, books that came under the harshest criticism of the critics. By cover date May/48 Gleason had published a "code" of conduct to be followed in his crime comics Crime Does Not Pay and Crime and Punishment.

Mr. Harvey Kurtzman "suggested that comic books should be improved and made educational". Kurtzman was one of the very few true geniuses of the industry, creating some of the cultural high points of the medium as MAD COMICS and TWO-FISTED TALES. What's interesting is the fact that at the time of this symposium (March 19, 1948), Kurtzman was mainly freelancing at Timely, producing his Hey Look! filler and trying to find his artistic footing in the industry. How he came to be associated with this symposium is unknown to me.

Mr. Harold Straubing is identified as a "Comics Editor, New York Herald Tribune", who defended comic books stating: "Whether the responsibility for a delinquency rests with the comic book influences is doubtful, because we are exposed to so much crime, violence, conflicting ideas and social problems in life and other mediums of expression". Straubing (1918-1994) was a writer at Timely at this time, having worked around the industry previously as well as in the animation industry. He would later join the Lev Gleason staff and do extensive writing for magazines and books.

Lastly, on the approximate 50 year anniversary of the symposium (1998), Arnold M. Ludwig, M.D., then Professor of Psychiatry, University of Kentucky Medical Center, Lexington, KY, made some contemporary comments I'll put below. Also is a link to the text of the entire symposium as well as the below comments at the end.

COMMENTS ON FREDERIC WERTHAM, M.D., ET AL.:

"THE PSYCHOPATHOLOGY OF COMIC BOOKS": A SYMPOSIUM

"It is remarkable that almost 50 years ago, the Association for the Advancement of Psychotherapy had the foresight to sponsor a symposium on the subject of comic books. After reviewing the comments in this symposium, I am struck by two things: how much times have changed, and how the present reflects the past."

"Back in the 1940s, comic books held mass public appeal, especially for children. Nowadays, modern technology has revolutionized this medium of expression. The cartoon characters that once roamed the comics, along with many new ones, not only can be found in animated television series and arcade games but also now interact with the viewers through computer-generated programs and may be portrayed by live actors in the movies. Once virtual reality becomes a reality, the make-believe and the real are likely to blur further. Despite these radical changes, many of the issues seem the same. Many mental health professionals still express grave concern about the explicit violence, sadomasochistic themes, and negative stereotyping in comics, video games, and animated films and their potential detrimental effects on children and society. Certain activistic groups seek legislation to regulate the kinds of information that can be disseminated to impressionable youths. Many people fear that comics convey a false sense of values and a distorted view of reality. Remarkably, all of these issues as well as others surface in this symposium that was held almost a half-century ago."

"The topics covered in this symposium are varied. Gerson Legman makes some interesting observations about some of the reasons for the growing popularity of comic books. Hilde L. Mosse comments on the role of aggression and violence in fantasy and fact. Paula Elkisch describes the results of a survey on children about the time they spend reading comics and their opinions about them. And Marvin L. Blumberg documents some of the bad influences of comics on children. Since comics represent an integral part of our culture, these issues continue to have relevance to psychotherapy, especially with children. The discussion following the symposium brought out valuable points. Johann G. Auerbach's statement that comics in contrast to fairy tales lack the fantasy element that helps the child get rid of aggressive feelings is, I think, an important distinction."

"Yet time and reflection do allow for a broadening of perspective. Because of the persistence and mass appeal of comics within many media of expression, we are obliged to wonder what purpose they serve in society and what individual needs they meet. As adults, do we ever outgrow our childhood need for heroes and villains, our fascination with violence, our desire for mastery, and our tendency to think simplistically and stereotypically? As parents, are we secretly thankful for the magnetic appeal of comics, which lets them serve as surrogate babysitters for our children? Most important, do our criticisms of comic books and related media represent an objective judgment of their worth or simply a reflection of our values and an expression of our frustrations with society? Unfortunately, answers to these questions won't be found in the series of articles written for this symposium, but some interesting observations will."

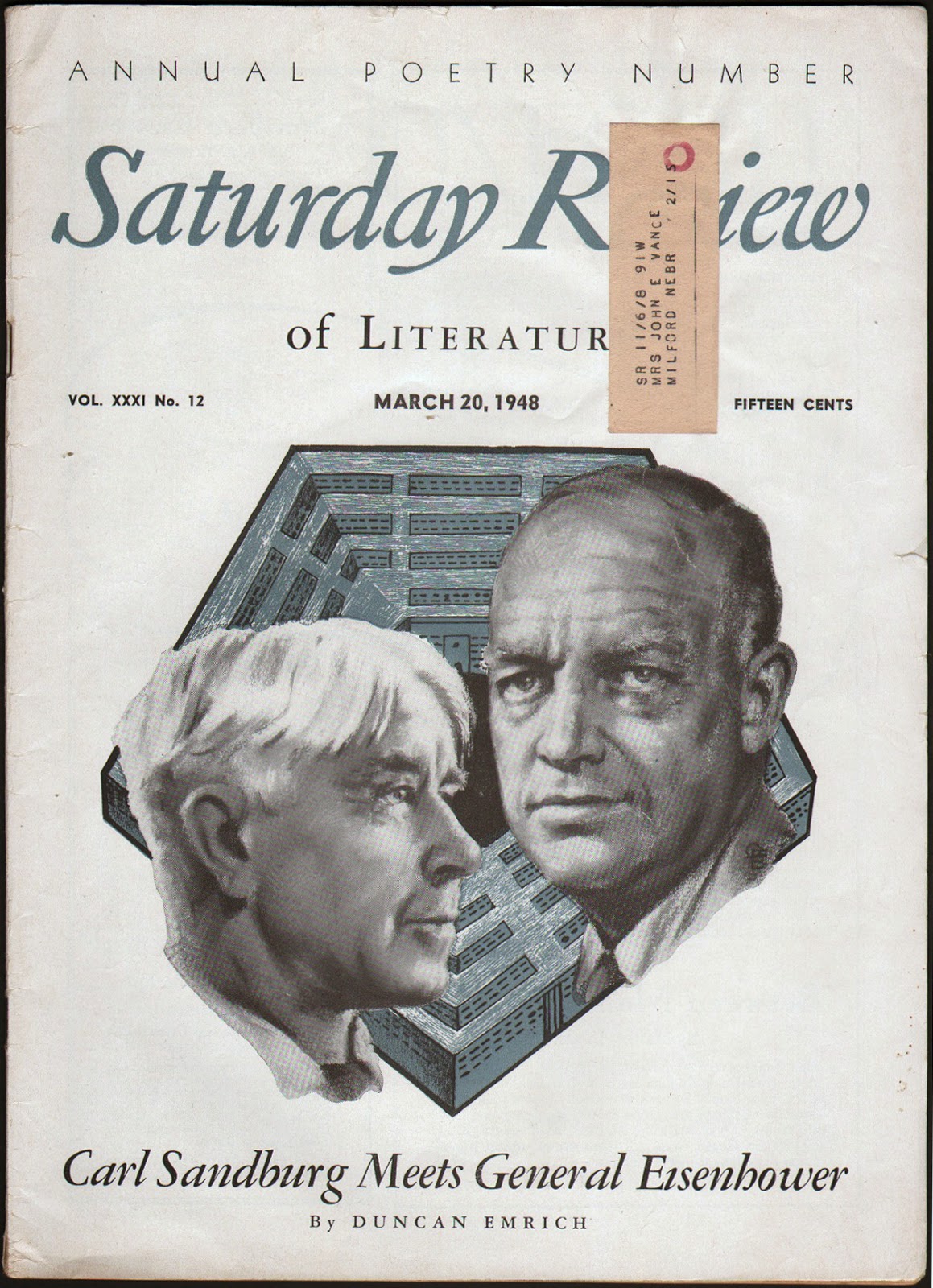

Within a week of the conclusion of the above symposium, the media began to get involved. The March 20, 1948 issue of the Saturday Review of Literature had an article by John Mason Brown titled "The Case Against the Comics".

Under the heading

"American Comics Become A Battlefield", a

double page spread on pages 30-31 presented the dichotomy of William Lass praising the recent half-century of newspaper comic art as an artform on the one hand, while John Mason Brown skewers comics during a debate with cartoonist Al Capp, on the other hand (in a reprint of his opening statement over the radio program "America's Town Meeting - What's Wrong With Comics").

Brown presents a horrendously biased and ignorant rant on the cultural and artistically bankrupt artform known as sequential art, whether it be newspaper comics or even worse, comic books.

The same article had a rebuttal by cartoonist

Al Capp of

Li'l Abner fame, titled

"The Case For Comics", where he uses the same reasoning tactic that will be co-opted shortly by David Pace Wigransky and Stan Lee, in both his future Timely editorials and his 1953 anti-Wertham story "The Witch in the Woods" published in

Menace #7 (reprinted in part 2 to follow).

The very next week came a scathing article in the March 27, 1948 issue of

Collier's Weekly titled

“Horror in the Nursery” by

Judith Crist, laying out Wertham’s ideas. This is the same Judith Crist who would become one of the most famous film, drama and television critics, writing for the New York Herald-

Tribune, NBC Today Show and TV Guide.

With the symposium date of March 19, Crist and The New York Herald Tribune covered the meeting two days later on March 21 in an article in the newspaper titled "Comic Books Dissected at Psychiatric Forum". The Collier's article is dated March 27, 1948 and the author is thoroughly familiar with the recently completed (but unpublished) "Psychopathology of Comic Books" symposium, including all the important points and recommendations made by the participants. Crist is so familiar with the material it makes me wonder whether she attended the symposium, perhaps even invited as a media liaison by Dr. Wertham. An alternative scenario is that Wertham reached out to the media, informing them of the recent symposium, and providing all the ammunition needed to get the ball rolling in the public's eye. The irresponsible "staged" photo above is purely intended to incite, doing to impressionable parents exactly what the article claims comic books were doing to "impressionable" children.

Crist lays out Wertham's impressive credentials and case histories involving juvenile crime and the reading of comic books, conceding a distinction that while every child who read comic books didn't go on to perform violent acts, all juveniles who "do" perform violent acts read comic books. If comic book reading was causing a population increase in juvenile crime, then my big question to the society of the 1940's is where were the parents?

When did I miss the fact that parents of the 1940's were "absent", "non-involved" with their children and horrendously neglectful of their offspring's emotional and developmental needs? The answer is I didn't miss this fact. The vast majority of the children of this time were just fine, normal kids. Wertham dealt in his professional capacity with the tiny percent of the child population who were "troubled". The leap in logic and projection across the entire demographic, in retrospect, was wrong, his graphic case studies notwithstanding.

Crist then relates more on the symposium's concern with the female child and the alleged fact that images of women with "full bosom and rounded hips", along with the comic book violence, are dangerous to the adolescent girl's "fear of sex and her sometimes resulting frigidity". Jeez! Who knew???

We further find that Wertham reserved his harshest criticism not to the comic books themselves, but to his fellow professionals who served as "consultants" to comic book companies, proving in his own words "the unhealthy state of child psychiatry". Wertham

was right about this, only in my opinion, it wasn't exactly what he had in mind. So this boils down to his stand being "I'm right and any contrary opinion, even by an equally credentialed professional colleague in my field, is still wrong". Or even more succinctly

"I'm right because I say so".

But you know what really disturbs me the most? The fact already covered in the symposium and reiterated here where Dr. Wertham bashes "apparently harmful children's animal comic books", meaning the newsstands funny animal titles where anthropomorphic forest creatures engage in "undue amounts of socking over the heads and banging in the jaw" as well as "toys that come to life at night sometime put in the time strangling one another". With this incomprehensibly ridiculous tough stance, Wertham has not only vilified funny animal comics, but in the age right before television, also has ostensibly slammed the entire breadth of all the major motion picture film's animation studio's output, from Disney, MGM and Warner Bros., to Walter Lantz, Terrytoons and Paramount. Imagine his indignation upon seeing children in a theater audience watching a violent Popeye cartoon. Imagine his consternation upon seeing children enjoying the frenetic, violent antics of Tom & Jerry or Heckle & Jeckle. And just imaging his absolute detestable horror and revulsion upon seeing children "laughing" at a violently over-the-top Tex Avery cartoon. All of these, including Bugs, Daffy, Mickey and Donald, engage in cartoon violence in which the principal consumers were children.

But while I'm sure he disapproved of the animated cartoons, Wertham did not go after film's animation studios to any real degree, at least not to my knowledge, even though children were as voluminous a visual consumer as adults were. He went after the easiest, default medium. The path of least resistance. The environment that could not fight back easily. The lowly comic book industry.

The rest of the article covers complaints we've already seen:

- "comic books are optically hard to read with garish colors and semi-printed balloons"

- "they retard children's reading skills"

- "comic books make children reluctant to read"

- "delinquent youngsters are almost five years retarded in reading abilities"

- "children of families in which lower income is hand-in-hand with lower intellectual standards are the most omnivorous comic book readers"

- "the books distract him from his lessons"

All of the above silly pronouncements can easily be refuted:

- Comic books will now join film before and television after, as the latest medium to "ruin" junior's eyes.

- Comic books likely will "enhance" children's reading abilities.

- Comic books probably made children want to read "more"

- Delinquent youngsters are surely "behind" the reading curve and not scholars to begin with.

- Lower income families likely stressed education less in their children. Wertham's point is that the poor and uneducated read more comic books. I don't believe this has ever been proven.

- Where are the parents??? If a kid is not paying attention, take his comic books away! Television will become the next "big distraction" to junior's lessons.

The piece ends with calls to "local enforcement of the penal codes by District Attorneys" and the "prosecution of anyone offering for sale" the offensive material. As we see this early on, Wertham wanted "legislation" to enter the picture.

Time Magazine then weighed in with this article in their March 29, 1948 issue, basically regurgitating various ideas from Wertham's symposium.

Judith Christ continued and followed up in the May 9, 1948

New York Herald Tribune.....

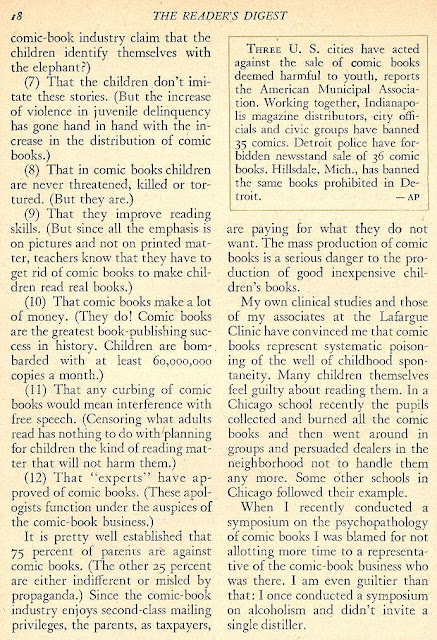

Fredric Wertham wasn't finished, though. With the media getting more interested, he takes the ball into his own hands. In the Saturday Review of Literature dated May 29, 1948, Wertham came out with guns blazing with “The Comics …Very Funny!”. Wertham now pushed his condemnation of comic books, specifically crime comic books, even further onto the public’s radar in a major article, a cover story written by Wertham himself.

|

|

SATURDAY REVIEW OF LITERATURE, May 29, 1948

|

Just read the opening paragraph! A mother consults with Wertham, frantically and anxiously relating that her four year old daughter was being roughed up by small boys in her apartment building, boys aged 3 to 9. Three to nine! They hit the girl, tie her up with rope, push her, etc. Now I ask, what mother places her 4-year old daughter "unsupervised" in the play care of rowdy, strange children? I have a daughter who is now 19. When she was 4 years old she wouldn't be out of our sight. This is plain and simple a case of poor parenting. The answer lies anywhere from not allowing the young girl out unsupervised to speaking to the parents of the unruly children. Today, this woman would be reported to Child Protective Services.

|

|

SAT. REVIEW OF LITERATURE, May 29, 1948, p.6

|

Case study after case study, the scenario is the same. A young child engaging in maladjusted behavior, completely unsupervised by any sort of parental authority. Perhaps the problem was the parenting methods employed rather than the children reading comic books. Perhaps many of these children were extreme developmental behavioral situations that today would be diagnosed differently as ADD/ADHD or a wide spectrum of autistic scenarios, childhood behavior problems unheard of in that day and age, many of which are treated with medication today. If we consider roughly two million children today are diagnosed under the umbrella ADD/ADHD alone, projecting back to 1948 we can surely consider a percentage of children with the same undiagnosed behavioral problems.

Wertham keeps pushing the envelope to ridiculous heights. A 13 year old boy who is a "real comic book addict", who likes ray-guns that shoot out rays and kill people, something any science-fiction loving child of today, or western loving child of yesteryear, would relate to. What did Dr. Wertham think of Star Wars, I wonder? A lot of ray guns killed a lot of people in that film! Wertham speculates if the ray gun is a "phallic" symbol.

I suppose hindsight is 20/20 but from today's viewpoint, having gone through the rock and roll / youth culture era, the 1960's counter-culture revolution, political assassinations and a presidential resignation, home video, video games, the internet, cell phones, texting, Youtube and Facebook, my perception is still that children are children and pretty much the same from generation to generation, albeit much more sophisticated at a younger age than their generational predecessors. There are still bullies, although the methods are changing from physical confrontations to "digital" targeting. There is less "parental" supervision today than ever before as overwhelmed two salary families turn junior over to electronic babysitters every day, not only the television of my generation but today's video games and computers. Yet, children are the same children with the likely same percentages of problematic behavior.

|

|

SAT. REVIEW OF LITERATURE, May 29, 1948, p.7

|

Wertham next refers to John Mason Brown's article in the previous week's Saturday Review where Brown refers to comic books as the "Marijuana of the Nursery". My response is rather than blame the comic books, blame "The Collapse of Good Parenting Skills".

Finally, Wertham gives 17 points in favor of comic books that he complied probably from various industry and professional sources. He snarkily and sarcastically then refutes each one, many with responses that would not hold up to critical scrutiny and debate. Point #2 is very telling. He states that one "support" for comic books is the fact that "if a child is bad, it's the child's fault as being inherently bad, neurotic or disturbed". Rather than even consider the possibility that these children could have real behavioral problems with a medical cause, Wertham obliviously draws a comparison to the owner of a rabbit-killing dog blaming the rabbit for starting the fight resulting in the rabbit's death. Apples and oranges. The remaining 16 points "supporting" comic books are similarly trashed and can be read in the scans I've provided.

|

|

SAT. REVIEW OF LITERATURE, May 29, 1948, p.27

|

|

|

SAT. REVIEW OF LITERATURE, May 29, 1948, p.28

|

|

|

SAT. REVIEW OF LITERATURE, May 29, 1948, p.29

|

Wertham closes mentioning his recent symposium and his impressive credentials are listed at the end. The illustrations accompanying the article are equally telling. Three are reproduced on the second page with captions blaming them for the fall of western civilization, although while I must say that the "injury-to-eye" panel is pretty intense, it's likely the most extreme graphic example Wertham could find and not what little Johnny was regularly exposed to by any means. That panel was taken from the incredible Jack Cole story "Murder, Morphine and Me! from True Crime Comics #2 (May/47) and has become the standard bearer for all that was wrong with comic books ... graphic violence, brutality against women and a narcotics storyline. The fact that the panel below was a dream sequence and didn't actually happen, coupled with the plot being a morality play against the dangers of crime and drugs with the bad guys getting it in the end, didn't matter. Today the story is considered a masterpiece of composition and a pre-code icon of mid-century cultural significance.

|

|

Jack Cole TRUE CRIME COMICS #2 (May/47) Page 2, panel 6

|

|

|

Jack Cole TRUE CRIME COMICS #2 (May/47) p.1

|

|

| Jack Cole TRUE CRIME COMICS #2 (May/47) p.2 |

The Chicago Tribune carried a story on April 22, 1948 about a plan put in place to set up a censor board. Here is the first column:

|

| CHICAGO TRIBUNE April 22, 1948 |

The New York Times ran articles covering the controversy throughout 1948:

|

|

NEW YORK TIMES June 24, 1948

|

Throughout the country the debate raged in print:

|

|

CHICAGO TRIBUNE February 20, 1948

|

The Chicago Tribune reported on July 2 that a six-point code of editorial standards was adopted by some comic book publishers as a self-policing measure, foreshadowing what was to come in another seven years. These six points attempted to rule out the most violent scenes, portrayals and situations in comic books.

|

|

CHICAGO TRIBUNE July 2, 1948

|

|

|

CHICAGO TRIBUNE October 26, 1948

|

|

|

CHICAGO TRIBUNE December 16, 1948

|

Tired with the incessant outcries and accusations from all fronts charging comic books with contributing to the rising rates of juvenile delinquency, the industry begrudgingly reacted to the growing hysteria. In July of 1948, thirty-five comic book publishers formed the Association of Comic Magazine Publishers (ACMP), with George T. Delacorte of Dell as their president. All the major comic book publishers joined this loose affiliation except Gilberton, who published Classics Illustrated, and DC, who had an Editorial Advisory Board of professionals in education and child welfare including Pearl S. Buck and William Moulton Marston. Both publishers felt their membership unnecessary. The ACMP, although established with high intentions, found itself mostly ineffective and would lose members as the years went on.

Timely’s response was immediate. Publisher Martin Goodman and editor-in-chief Stan Lee responded

with two full-page editorials. The first, in November and December 1948 cover-dated issues, addressed their concern with the media’s criticism of comic books and countered that they obtained editorial advice from Dr. Jean Thompson, a psychiatrist in the Child Guidance Bureau of the New York City Board of Education, and likely someone that Dr. Wertham considered part of the problem as a comic book apologist. Dr. Thompson’s name was placed at the bottom of page one in bold black letters, signaling that Marvel Comics were “above criticism,” which interestingly revealed that internally, the company was calling itself “Marvel Comics” at this time, not Timely Comics.

|

|

1st Editorial from November and December 1948 cover dated issues

|

A second full-page editorial appeared in January through March 1949 cover-dated issues (on the newsstands starting Fall of 1948). This editorial directly addressed the raging debate about comic books in the pages of the aforementioned Saturday Review and pointedly mentions Dr. Wertham by name this time. The editorial quotes a letter from the July 24th issue by David Pace Wigransky, a 14 year old comics reader, who intelligently and logically refutes Wertham, explaining that finding a juvenile delinquent as a comic reader proves nothing as the vast millions of America’s youth who read comics are “not” juvenile delinquents. The editorial ends with a claim that Marvel Comics are “good comics” and again touts Dr. Thompson’s endorsement on the first page of every comic they published, strategically countering like a chess game, pitting one psychiatrist against another.

|

|

2nd editorial from January through Mar/49 cover dated issues

|

|

|

SATURDAY REVIEW, July 24, 1948

|

I present 14 year old David Wigransky's letter below, "Cain before Comics". Following it are several other letters from readers commenting on comics and their labeling as "bad" by Dr. Wertham. After the publication of John Mason Brown's article "The Case against the Comics" in the March 20th issue and Dr. Wertham's screed "The Comics...Very Funny" in the May 29th issue, the debate was carried out into the "letters to the editor" page. This culminated with the David Wigransky letter in the July 24 issue. David's letter needs a little more scrutiny. The editor's note to the letter page gives the background on the debate and sets up the letter. He also informs us that the letter copy has not been edited but sections were omitted for space considerations. This means that the original letter was much longer:

"Of the numerous replies we have received, one of the most interesting is that written by fourteen-year-old David Pace Wigransky of Washington, D.C. Young Mr. Wigransky, who has just completed the tenth grade at the Calvin Coolidge Senior High School, is a devoted reader and collector of comic books. He tells us that he now owns 5,212 such books and intends to make drawing for them his profession and life's work".

"Unlike other critics of comics," Mr. Wigransky writes, "I possess a first-hand knowledge of them, and unlike even those critics who argue in their favor, I can say that I was once an average, normal comic-book fan and reader, during the war and before it. Therefore i feel that I am more qualified than people like John Mason Brown and Dr. Wertham in criticizing them".

|

|

SATURDAY REVIEW OF LITERATURE, July 24, 1948 [David Wigransky letter]

|

|

|

SATURDAY REVIEW OF LITERATURE, July 24, 1948 [David Wigransky letter]

|

A careful reading of David Wigransky's letter immediately reveals to me one thing. In my opinion, this was "not" written by a 14 year old boy. The letter is immaculate! It carefully refutes, rebuts and counters nearly every point Dr. Wertham has made in his previous published comic book denouncements. In fact, it reads like a legal brief, written by a lawyer for a comic book company preparing to go to war with Dr. Wertham and his anti-comic book ilk. While no one has ever made a case for anyone other than Wigransky himself being the author (and apparently a check with David's high school principal confirmed his writing skills), I just find it hard to believe that a 14 year old wrote this all by himself.

|

|

14 year old David Pace Wigransky

|

Wigransky opens the letter with a biblical quote from Genesis 4:8 : "And it came to pass, when they were in the field, that Cain rose up against Abel his brother, and slew him.", using this quote to present the fact that the world's most widely read book, The Bible, was rife with violence and fratricide. Next is the mention of a 1924 brutal murder case involving well-to-do teenagers who read "good books", asking Dr. Wertham to explain how such could occur in the era "before" comic books.

Wigransky goes on to mention that 69 million perfectly, happy, normal American boys and girls read comic books to no ill effect and that Wertham is basically loading the deck with his 25 depraved criminal juvenile case studies, asking them leading questions, all with the mission to get them to mention comic books during their "psychoanalysis" with the doctor.

Next comes a history lesson on the crusade against comics hailing back to Richard Outcault's The Yellow Kid in 1896 and the subsequent nomenclature "Yellow Journalism" stemming from such low-brow culture. An analysis of Wertham's child psychiatric methods are called into question, offering that rather than coming across as a superior, authoritative figure, Wertham (and his ilk) should view children through a child's eyes.

He ends with the statement that in "spite" of Wertham's beliefs, the present generation of children will turn out just as well as the preceding generation, raised before there were comic books.

Several letters following Wigransky's are quite interesting:

- A mother from St. Lawrence congratulates Dr. Wertham on his article and agrees with the evils of comic books, hoping that the article sways public opinion against comic books.

- Another mother from Kansas City didn't realize comic books were as bad as they apparently were and wants to know what she and other mothers can do about it, stating she can't stop her son from reading them, although she hasn't noticed any change in his behavior yet..

- A third mother, the wife of a psychiatrist in Colorado Springs, states a fervent "Amen"!

- A woman from St. Paul wants to start a campaign against comic books among parents and teachers, noticing that while the children aren't criminals, their language and attitudes definitely deteriorate subsequent to reading comic books.

- And finally, the most hilarious letter of all! An E.M. Hunt from White Plains, NY, writes that while some comics may be bad in spots, the Bible is even worse for children! He relates how a local 4 year old girl likes Bible stories "where God kills all the little babies" and other favorites "where the boys throw Joseph down the well" and "where God has the men kill Jesus". Mr Hunt then states that while the wrong kind of comics are bad for children, "so is the wrong kind of religion", and that "they would be better off without "any" comics or religious stories", continuing "As long as it is profitable for the trade to sell bad comics and for the churches to furnish low-grade religion, the children will be supplied with both products."

Who actually wrote the Wigransky letter and the machinations behind it are unfortunately lost to history. Artist and historian Michael T. Gilbert, writing in Alter Ego #90 (Dec/09), notes that David's letter was later mentioned during the 1954 Senate Subcommittee meetings and never did make his career in comic books as he'd hoped but did become a published author, writing a book called Jolsonography, devoted to Al Jolson, in 1969. Gilbert also tracked down a fellow Jolson aficionado and entertainer, Clive Baldwin, who briefly met Wigransky in 1968, spending some time at his house where Wigranski lived with his mother. David died in 1969.

One last bit of David Wigransky history. Heritage Auctions recently sold the original Simon & Kirby cover art to Headline Comics #25 (July/47). Written at the top in the area where the logo is stripped off is the inscription "To David Wigransky - Best Wished and Good Luck "Joe Simon", Jack Kirby". It appears David had fans in Simon and Kirby and they sent him one of their crime covers as a thank you for backing the cause of comic books.

|

|

HEADLINE COMICS #25 (July/47)

|

As the forces aligned against the comic book industry, a third editorial appeared in the April and May, 1949 cover dated issues. In this one Stan Lee and Martin Goodman likens the anti-comic book hoopla to the voices of the 18th century book-banning establishment that attempted to ban books like Robinson Crusoe. The point being made is one of "rights", as in the reader has the "right" to decide what he/she wants to read and doesn't need anyone telling them what to do. Dr. Jean Thompson is again touted as Marvel's "seal of approval."

|

|

3rd editorial from April & May 1949 cover dated issues

|

And finally, a fourth editorial the following month. Lee and Goodman once again mention literary titles of note (Robin Hood, The Iliad, Tom Sawyer) in their attempt to explain to the young readers that their "right" to choose their own reading matter is being infringed upon.

|

|

4th editorial from June & July 1949 cover dated issues

|

By Timely's Dec/49 cover dated issues, publisher Martin Goodman and editor-in-chief Stan Lee further tried to distance themselves from the swirling hysteria, now touting their "Marvel Comics" line as "good reading". They brought back Goodman's old Red Circle-like pulp colophon from the late 1930's, now a circular Marvel Comics bullet on the cover of nearly every issue published between cover dates Feb/49 and June/50, (Dec/48 and Feb/50 "real" time). Dr. Jean Thompson is prominently displayed in the ad:

|

| ad from WESTERN WINNERS #7 (Dec/49) |

While Dr. Wertham and the anti-comics hysteria received a large part of the media’s coverage, behind

the scenes, especially in academia, the verdict was still out whether comic books were truly as negatively

influential as Wertham claimed. For every Wertham there was another professional who disagreed. In

1948 the New York Times published a series of articles spotlighting this debate. In “Parents are Warned Not to Blame Comic Books for Juvenile Crime,” Mr. Edwin J. Lukas, executive director of the Society for the Prevention of Crime, declared comic books 20th century scapegoats, shifting parents’ own responsibilities away from themselves in the matter of juvenile delinquency.

|

|

THE NEW YORK TIMES, October 7, 1948

|

Another New York Times article in February 1949, “Status of the Comic Book”, laid out the entire breadth of comic books and challenged parents to become involved with their children’s reading, emphasizing the many positive attributes of comic books.

|

|

NEW YORK TIMES February 6, 1949

|

In 1949, COMMENTARY magazine, (ahem) ... "commented" on the controversy, publishing an article in the January 1949 issue titled "Comic Books and Other Horrors" by Norbert Muhlen (1909-1981), who would go on to write several important books on financial backing of the Nazi rise to power in Germany. While critical of the violence found in comic books, Muhlen was equally critical of Werthan's "evidence" and the article did not present as a support for Wertham. In the February issue, a letter from Dr. Fredric Wertham was published and followed by an answer by article author Norbert Muhlen:

To the Editor:

I would like to correct two inaccuracies concerning my own opinion of comic books, as represented by Norbert Muhlen's article “Comic Books and Other Horrors” [January 1949].

First, Dr. Muhlen states—in an attempt to show a contradiction—that “Dr. Wertham himself rejected this simplistic theory of causation,” [when he wrote in his book Dark Legend:] “Apparently anti-social impulses do not originate in that way.” I have never advocated any “simplistic theory of causation.” I do not claim that juvenile delinquency “originates” in comic books. On the contrary, in my article in the Saturday Review of Literature, “The Comics—Very Funny,” from which he quotes, I state very clearly: “We are getting to the roots of one of the contributing causes of juvenile delinquency when we study the influence of comic books.”

Secondly, Dr. Muhlen misquotes me. He attributes to me the statement that “the increase in juvenile delinquency has gone hand in hand with the distribution of comic books.” That is not what I wrote. What I did write (in the same article in the Saturday Review) is that: “The increase of violence in juvenile delinquency has gone hand in hand with the increase in the distribution of comic books.” That is something very different.

I think it is significant that the author of your article leaves out the very word “violence” in the sentence he quotes, just as so many people nowadays leave out the subject of violence, which I consider one of the most important problems of our time.

Fredric Wertham

New York City

To the Editor:

Whether the subject of violence is or is not one of the most important problems of our time, it certainly is the basic problem of comic books, as I attempted to show in my article, in which the word

“violence” recurs twenty-six times. This figure might be censured by a professor of journalism, but it certainly answers Fredric Wertham's strange reproach that I did “leave out the subject of violence.” As a matter of fact, the very conclusion of my article was that mass entertainment by violence tends to become the child's education to violence.

I disagreed, however, with Dr. Wertham's often-repeated opinion that “comic-book reading was a distinct influencing factor in the case of every single delinquent or disturbed child we studied. And that factor must be curbed as it steadily increases”. (Collier's, March 27, 1948.) Dr. Wertham asks for censorship against the comic books; this infringement upon the freedom of the press is—logically as well as legally—based on his opinion that the comic books present “a clear and present danger” as one cause of juvenile delinquency; and he claims to be able to prove his point by-so far unpublished—case material.

While preparing my article, I asked Dr. Wertham to give me an opportunity to let me see the case material on which his opinions are based. Dr. Wertham replied that “it is physically impossible for us to comply with [such a request]. As far as I know there are quite a number of people in different parts of the country wishing to write the type of article you propose.” Without access to his materials, I based my conclusion on my own socio-statistical deduction that his charges against the comic books are not verifiable and not corresponding to the facts.

Norbert Muhlen

New York City

The very next March 1949 issue had a very long rebuttal by National's editor Whitney Ellsworth:

To the Editor:

I should like to offer some comments on Norbert Muhlen's article “Comic Books and Other Horrors,” in the January COMMENTARY.

Dr. Muhlen makes a great distinction between the “older, much-censored, and more refined newspaper comic strips,” and the “dehumanized, concentrated, and repetitious showing of death and destruction” in the comics magazines. Actually, no such wide dissimilarity exists. I have no desire to enter into internecine warfare with our “respectable” newspaper counterparts, but I offer that Dick Tracy, Kerry Drake, and a number of other crime strips are every bit as brutal and gory as anything that might be found in even the most violent comics magazines. Li'l Abner and Steve Canyon certainly capitalize upon the female form divine—nor does their sexiness exist only in the art work; the story situations point in the same direction. Vulgarity exists in Li'l Abner's hairy, spitting, burping characters, and also in such characters as B. O. Plenty in Dick Tracy—againPrince Valiant often sheds considerable amounts of visibly red blood. . . . And the examples I have cited are by no means unique. to mention only a couple of examples. The superbly drawn

Dr. Muhlen, commenting on the possibility of the reader identifying himself with the fictional hero, writes: “The symbol of this theory is the little boy who got a Superman cape on his birthday, wrapped it around himself, and sprang out of the window of his apartment house.” Just where the boy got the Superman cape is a mystery to us, since we never manufactured, nor authorized manufacture of, nor ever heard of any unauthorized manufacture of a Superman cape. This notwithstanding, the premise itself is not very solid. I knew, in my own youth, a highly intelligent boy of twelve who leaped from the rooftop of his parents' three-story brownstone house with an umbrella in lieu of a parachute. The fact that he was fortunate enough only to break both legs is probably more important than the fact that his act predated the adventures of Superman by more than two decades. There were foolish children before comics, and juvenile delinquents too. Official Federal Bureau of Investigation figures quote a substantial falling off of the juvenile delinquency rate in the last three years.

Of course it is hardly necessary to make the comparison between comics magazines and some of the so-called classics and semi-classics which many people suggest as a substitute for the comics. The fairy tales are replete with horror, fantasy, and gore. The classics similarly depict scenes of cruelty, murder, and mayhem. . . .

In reference to Dr. Muhlen's remarks on the efforts of certain publishers to apply self-censorship (and which he criticizes with considerable pessimism and sarcasm), let me point out that we, as one of the oldest and largest publishers in the comics magazine field, are heartily in accord with the movement to scrutinize comics. We are definitely opposed to those elements in the industry (even though they constitute a distinct minority) which publish tasteless comics. We at National Comics have been aware of our responsibility—long before there was any practical need to control, apologize, or defend. Our code has guaranteed outstanding comics reading matter from the point of view of story content, of legibility, and of good taste.

We do not deny the aid rendered by prominent professional persons—as a matter of fact, we are grateful for their excellent assistance. Our Editorial Advisory Board consists of such outstanding educators as Dr. Lauretta Bender, Associate Professor of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, New York University; Miss Josette Frank, Consultant on Children's Reading, Child Study Association of America; Dr. C. Bowie Millican, Department of English Literature, New York University; Dr. W. W. D. Sones, Professor of Education and Director of Curriculum Study, University of Pittsburgh; and Dr. S. Harcourt Peppard, formerly Acting Director, Bureau of Child Guidance, Board of Education, City of New York, and now Director, Essex County (New Jersey) Juvenile Clinic.

Rather than serving as mere “window dressing,” as Dr. Muhlen implies, the whole Board meets with the undersigned at intervals, and there is constant individual contact with its members. Miss Frank is in these offices several times a week. Dr. Bender and Dr. Peppard, both of whom are psychiatrists, are available for consultation. Dr. Sones makes continuing studies on such phases as the relation of comics to reading skills and vocabulary building; he comes to this office from his post in Pittsburgh at least once a month. Dr. Millican is at present on leave of absence to the United States Army with which he is serving as Colonel, in charge of the Information and Education Section of the Armed Forces in Germany.

This Editorial Advisory Board was formed in 1941 for the purpose of making professional recommendations to the editors, and has been of inestimable value through the years. The Board has no powers as such, but the professional standing and personal integrity of the individual members would preclude any possibility of their continuing to function on the Board if the publication failed to meet their high standards.

Dr. Muhlen writes: “This education to violence, while hardly presenting the ‘clear and present danger’ of causing juvenile crime waves, breaks the ground for a future criminal society. Individual insecurity and social anxiety, the common roots of both the murder trend in entertainment and increasing juvenile delinquency, can lead to brute force and terror. . . .” Might I remind Dr. Muhlen that during their training for combat, our soldiers were trained to kill; yet they did not continue to kill on their return to civilian status. Toy manufacturers have produced the simulated implements of war, yet I seriously doubt that they are guilty of instilling in children the desire to fight. We had juvenile delinquents before the advent of comics magazines, and among the many experts who have gone on record as contradicting Dr. Muhlen, let me add what Kenneth Warburton, Director of the Youth Counsel Bureau of the Bronx District Attorney's office, has to offer on the subject. The causes of crimes committed by juveniles, Mr. Warburton says, are broken homes, poverty, excessive drinking, and other unfavorable social conditions.

Whitney Ellsworth

Editorial Director

National Comics Publications, Inc.

New York City

To which Norbert Muhlen replied:

To the Editor:

If Mr. Ellsworth had read my article more carefully, he would have observed that I, too, objected to current sensational attempts to blame the comic books for juvenile delinquency. What I tried to emphasize was the more general, less acute effect of comic books—their tendency to encourage the acceptance of violence as the basis of human relations. Mr. Ellsworth does not even attempt to answer this point.

Scenes of cruelty characterize a minority of the newspaper strips, while they form the great mass of comic book content.

The story of the Superman cape was widely told two years ago. Si non è vero, è ben trovato.

Mr. Ellsworth states that “classics similarly depict scenes of cruelty, murder, and mayhem.” The basic dissimilarity in the effects of artistic productions and mass-produced, habitually-consumed comic books was extensively discussed in my article.

When Mr. Ellsworth compares the effect of his comic books to the wartime military education when soldiers were “trained to kill,” his opinion seems rather close to mine.

By 1949 the anti-comics hysteria wanes a bit and publishers begin to leave the ACMP. Timely may have left early on but at some point must have returned as their covers sported a small ACMP stamp from April 1952 to January 1955 on most titles.

1949 is also when Wertham published his book The Show of Violence, focusing away from comic books and into the world of violent crime and murder. Below is the 1951 paperback Eton edition.

1949 further showcased Wertham critics from the professional ranks.

The February 1949 issue of Family Circle magazine offered parents “What Can ‘You’ Do About Comic Books?”, a tempered look at what children were reading and offering a new approach to parents that refuted the outright distain from the Wertham-induced hysteria of 1948. This article is the most intelligent examination of the comic book problem of the era. Quite simply, the author asks mothers and parents to read the comic books their children are reading to familiarize themselves with the material and engage them as people rather than coming down with blanket hysteria. The piece logically asserts that many of the delinquent children whose case studies Wertham has proselytized about likely had deeper backgrounds ......

".... of emotional disturbances, of home rejection, elements that even without the stimulus of the comics, would have caused the children to run amuck And if these disturbed children hadn't picked up aggressive ideas from the comics, they would have picked them up from other sources - radio programs, movies, newspapers, crime magazines - or have created them out of their own imagination."

"The times are out of joint. Aggressive forces let loose in the world have caused two world wars and have started rumblings of a third. How can comic books be blamed (and some blame them almost exclusively) for an increase of violence and in delinquency?

"Our only safeguard is to help the young people entrusted to us to develop an emotional stability, a maturity, and a sense of values that will keep the comics in their place, as entertainment, release, or aid to education, to be outgrown in time for mature satisfactions."

To Family Circle magazine, all I can say is Bravo!

Similarly, the Public Affairs Committee in New York City, a nonprofit educational organization, published a pamphlet titled “Comics, Radio, Movies and Children” in which comics were “cleared” as an influence to delinquency. There may have been a later 1952 version of this booklet that included television:

The January 31, 1949 New York Times published an article stating that the anti-comics drive was waning and that romance comics (called "love" type comics) were replacing crime comics on the newsstands. While this may have been physically true, we all know what happened as the romance glut of 1949-1950 ended up with the near total collapse of the genre.

|

|

NEW YORK TIMES January 31, 1949

|

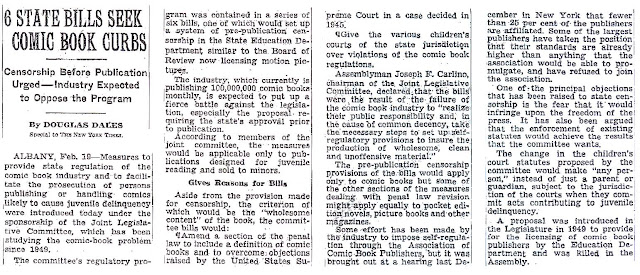

In 1949 the battle also got political. On the local level, the New York State Legislature adopted a resolution to study the publishers of comic books. The committee took testimony in 1950 and Wertham was closely involved as a psychiatric expert. The committee was renewed and continued through 1952, by now including TV, radio, magazines and paperbacks. Although battles were fought, the recommendations made were to defer to the status quo. The state level had failed Wertham.

In 1950 the federal government got involved as Senator Estes Kefauver was appointed chairman of the

Special Senate Committee to Investigate Organized Crime. Wertham tried to shoehorn comic books’ effect on juvenile delinquency into the proceedings, with minimal success. The New York Times reported a headline on November 11, 1950, “Many Doubt Comics Spur Crime, Senate Survey of Experts Show”. This piece summarized the Senate crime proceedings and noted celebrity testimony by the likes of J. Edgar Hoover and Milton Caniff, as well as Katherine F. Lenroot, chief of the Children’s Bureau of the Federal Security Agency, who called to the committee’s attention the code of ethics which 14 of the 32 comic book publishers voluntarily subscribed, and related that juvenile delinquency was the product of “manifold factors.” Wertham was certainly dismayed with the outcome. Here is an OCR'd version of the article:

|

|

NEW YORK TIMES November 11, 1950

|

Three days later a New York Times editorial again knocked Wertham back down. [OCR'd for clarity]:

|

|

NEW YORK TIMES November 14, 1950

|

Just to show that it was not just Wertham picking on comic books, the new medium of television was also in the crosshairs of the censors. From the December, 1951 issue of Writer's Digest, Lee Otis writing in his "Radio and TV" column.....

The TV industry has finally come up with a code to correct abuses in the business. By policing itself, the industry hopes to head off regulation from the outside. The code, drawn up by the Television Standards Committee of the National Association of Radio-Television Broadcasters, probably will be approved by the NARTB board of directors this month and will go into effect after the first of the year.The code provides for a TV “seal of approval” which stations may flash on the screen as long as they abide by the rules. And it sets up a six-man review board which will maintain a continuing review of all TV programming and have the power to revoke the seal if a station gets out of line. In this respect, the new code parallels the production code of the film industry. The TV code also follows the film code closely in the sections which deal with good taste and treatment of religious and minority groups. The words and phrases listed as verboten for TV are the same ones which are barred in movies.

Here are the highlights of the code as it applies to dramatic programs:

There must be no attacks on religion. If religious rites or ceremonies are shown, they must be presented accurately. When ministers, priests or rabbis appear as characters in scripts, they must be presented with dignity.

The sanctity of marriage and the value of the home must be upheld. Divorce should not be treated casually or justified as a solution for marital problems. Illicit sex relations are not to be presented as commendable; sex crimes and abnormalities are generally unacceptable; sex perversion must not be referred to.

Drunkenness or narcotics addiction should not be presented as desirable or prevalent. Liquor may not be shown unless it is required by the plot or for proper characterization. Gambling devices may be shown when they are necessary to the plot or for appropriate background, but gambling should be presented with discretion and in a manner which will not excite interest or foster betting.

Physical and mental afflictions and deformities should not be handled in such a way as to invite ridicule or offend sufferers, their families or friends.

Fortune telling, astrology, phrenology, palm reading and numerology are not considered legitimate sciences. When they are necessary to the plot, they should be presented in a way that will not foster superstition or encourage belief in them.

Cruelty, greed and selfishness should not be presented as worthy motives; neither should unfair exploitation for personal gain. Criminality must always be undesirable and unsympathetic; the techniques of crime must not be presented in such detail as to invite imitation.

Law enforcement should be upheld. Officers of the law are to be portrayed with respect and dignity. Murder or revenge as a motive for murder must never be justified. Suicide should not be treated as an acceptable solution for human problems.

The use of horror for its own sake is to be eliminated. No visual or aural effects which would shock or alarm the viewer are permitted. There shall be no detailed presentation of brutality or physical agony by sight or by sound. The code points out that television’s responsibility toward children goes beyond programs which are intended for children. Programs of all sorts which are scheduled at times of the day when children may be watching must avoid material which is excessively violent or would create morbid suspense.

The industry has been spurred towards self-regulation by such outside pressures as the Congressional bill proposed by Senator William Benton to set up a Citizens’ Advisory Board and the mounting complaints against television programming from both inside and outside the industry. CBS, for instance, toned down its Suspense program after several stations threatened to drop it. Programs like Lights Out, Danger and a whole raft of crime and mystery shows came under fire because of excessive use of horror and violence.

The sensitivity of the industry to mounting criticism was reflected in an incident at NBC-TV several months ago. A discussion of Lights Out was scheduled for NBC’s Author Meets the Critics program, which takes up movies and other mediums of entertainment as well as books. Lights Out was to be discussed pro and con by guest critics, with Producer Herbert Bayard Swope, Jr., on hand to defend the program. The debate was widely ballyhooed in advance, but, at the appointed hour, viewers who dialed NBC were informed than (sic) the discussion of Lights Out had been postponed because Swope was “indisposed.” It has never been rescheduled. Cynics are speculating that it suddenly occurred to NBC that this is no time for television to go around knocking itself.

In 1952 a second federal attempt against media violence was launched, this time in the House of

Representatives. Chaired by Congressman E.C. Gathings (after an aborted try in 1951), in May of that

year approval was gained to begin the Select Committee to Investigate Pornographic Materials, dealing

with television, radio, paperbacks and comic books. The hearings and testimonies eventually got around

to including horror comic books, which by this time (along with war comics) had supplanted crime comics as the dominant comic book genre being ravenously read by boys, and the final report recommended legislation to curtail the offensive material, all while some committee members were denouncing the committee’s own conclusions. The pressure on the various industries was real though, and racy paperback covers would be noticeably toned down as time went on. This would affect Martin Goodman also as he had his own line of paperbacks, Lion Books, with their own racy covers and plots. Here below we have two opposite examples of racy, inter-racial pulp fiction and their covers, subjects considered forbidden at the time in some segments of society.

|

|

PYRAMID BOOKS #102 (1953)

|

|

|

LION BOOKS #45 October, 1950

|

|

|

NEW YORK TIMES February 20, 1952

[To get to part 2, click "here"]

|

We further find that Wertham reserved his harshest criticism not to the comic books themselves, but to his fellow professionals who served as "consultants" to comic book companies, proving in his own words "the unhealthy state of child psychiatry". Wertham was right about this, only in my opinion, it wasn't exactly what he had in mind. So this boils down to his stand being "I'm right and any contrary opinion, even by an equally credentialed professional colleague in my field, is still wrong". Or even more succinctly "I'm right because I say so".

We further find that Wertham reserved his harshest criticism not to the comic books themselves, but to his fellow professionals who served as "consultants" to comic book companies, proving in his own words "the unhealthy state of child psychiatry". Wertham was right about this, only in my opinion, it wasn't exactly what he had in mind. So this boils down to his stand being "I'm right and any contrary opinion, even by an equally credentialed professional colleague in my field, is still wrong". Or even more succinctly "I'm right because I say so".

Wow! What a great collection of material and insights. Well done! I will definitely be sending my students here to check this out!

ReplyDeleteMake sure they check out part 2 by clicking on "older post" below! What do you teach?

ReplyDeleteMike,

ReplyDeleteGreat informative research, showing how far back censorship went. I thoroughly enjoyed this post.

On a lighter note...Y'know, its bad enough to go after crime and horror comics, but funny animals? I ask you, Dr. Wertham, have you no shame? :)